![]()

(1985)

| Characters | |

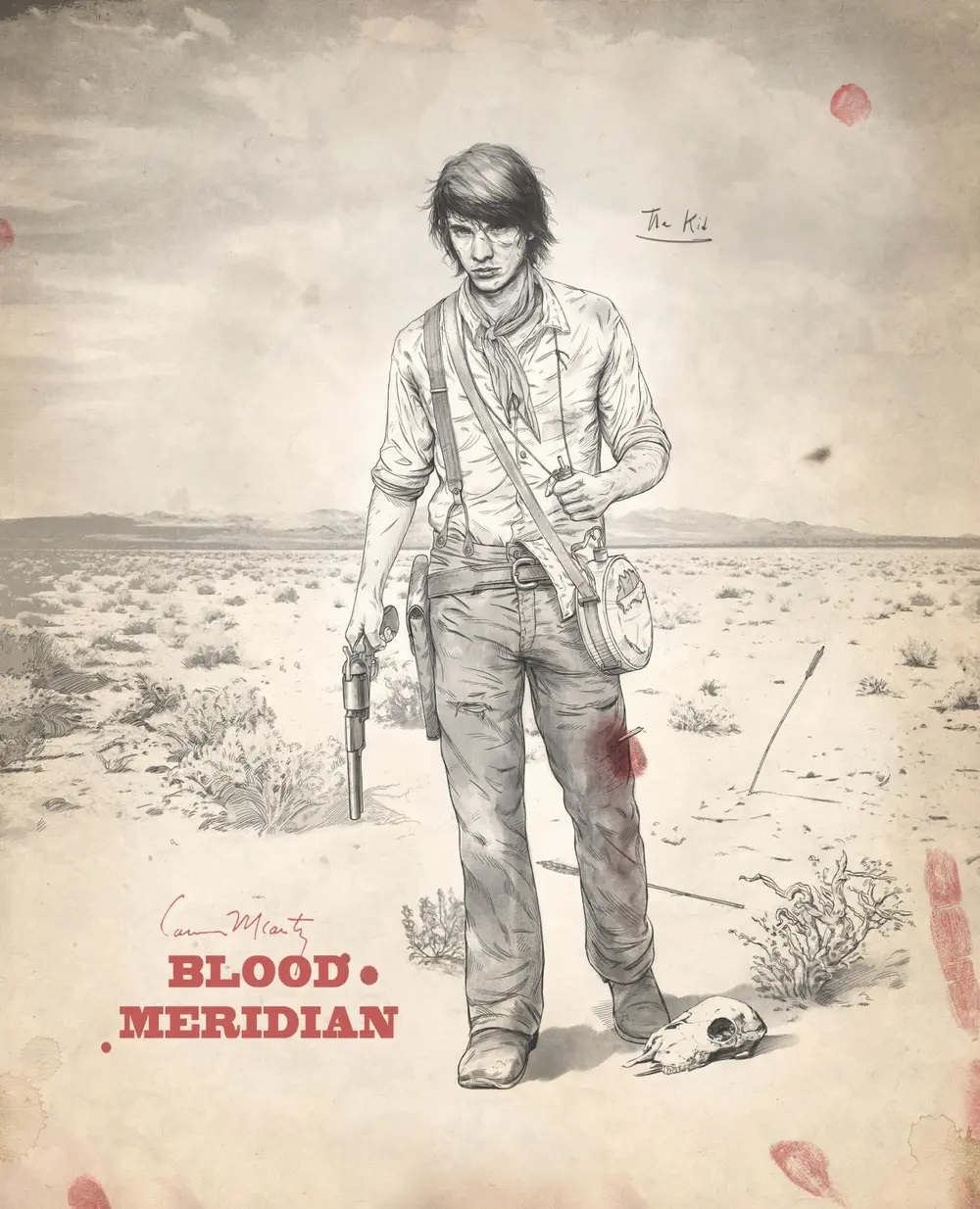

| The Kid | The novel's protagonist, if it can be said to have one, is the kid, but McCarthy shows us very little of the kid's actions and thoughts. Born in 1833 to a poor family in Tennessee, the kid has an innate "taste for mindless violence," and by the age of fourteen runs away from home to lead a dissolute and vicious life. Early on he falls in with Captain White's army during its unauthorized invasion of Mexico, which results in the army's destruction and the kid's imprisonment in Chihuahua City. However, he is soon set free to ride with Captain Glanton's gang of scalp hunters, contracted by the Chihuahuan government to hunt the Apaches. The kid proves himself an effective killer, yet, unlike his fellow scalp hunters, he also retains a shred of his humanity. He endangers his own life on several occasions to help and accommodate his comrades-in-arms, as when he removes the arrow from David Brown's thigh when none else would, or spares Dick Shelby's life in defiance of Glanton's orders. For these small acts of mercy, the Judge accuses the kid of violating the gang's amoral spirit of war for war's sake, of poisoning its enterprise. In 1878, at the age of 45, the kid (by then called the man), is discovered brutally murdered in a Texas outhouse after an encounter with the Judge. |

| Judge Holden |

Often called "the Judge", a totally bald, toweringly gigantic, supernaturally strong, demonically violent, and profoundly learned deputy in Glanton's gang, second in command to none but Glanton himself. The Judge fell in with the scalp hunters after he helped them to massacre their Apache pursuers with gunpowder he manufactured utilizing little more than bat guano and human urine. He is a studious anthropologist and naturalist, a polyglot, an eloquent lecturer in fields as diverse as biological evolution and jurisprudence. He is an expert fiddler and nimble dancer. He is also a liar, a sadistic killer, and very possibly a rapist and murderer of young children. The Judge has pledged himself absolutely to the god of war, going so far as to claim that war itself is God. Fatally severe on those who break partisanship with the god of war, the Judge finds his wayward yet antagonistic spiritual son in the kid, whom he accuses of poisoning the gang's enterprise by reserving a measure of mercy in his heart. The Judge is the only member of Glanton's gang to survive the novel; he claims that he will never die. |

| John Joel Glanton | The leader of the gang of scalp hunters featured in the novel, Glanton is a small dark-haired man who has left his wife and daughter for a life of bloodshed and debauchery. After the Judge saved his gang from the Apaches, Glanton entered into something of a terrible covenant with the Judge, who became his foremost deputy. Obsessed with the inexorable workings of fate, Glanton claims agency over his own end by self-destructively embracing it; after a bounty is posted on his head in Mexico, he becomes more and more possessed by a mad and explosive intensity, leading his gang on to the Colorado River where they violently betray Yuma Indians with whom they've conspired and seize Dr. Lincoln's ferry. The Yumas respond in kind, massacring the gang; Glanton dies at the hands of the Yuma leader Caballo en Pelo, and his corpse is hurled onto a bonfire. |

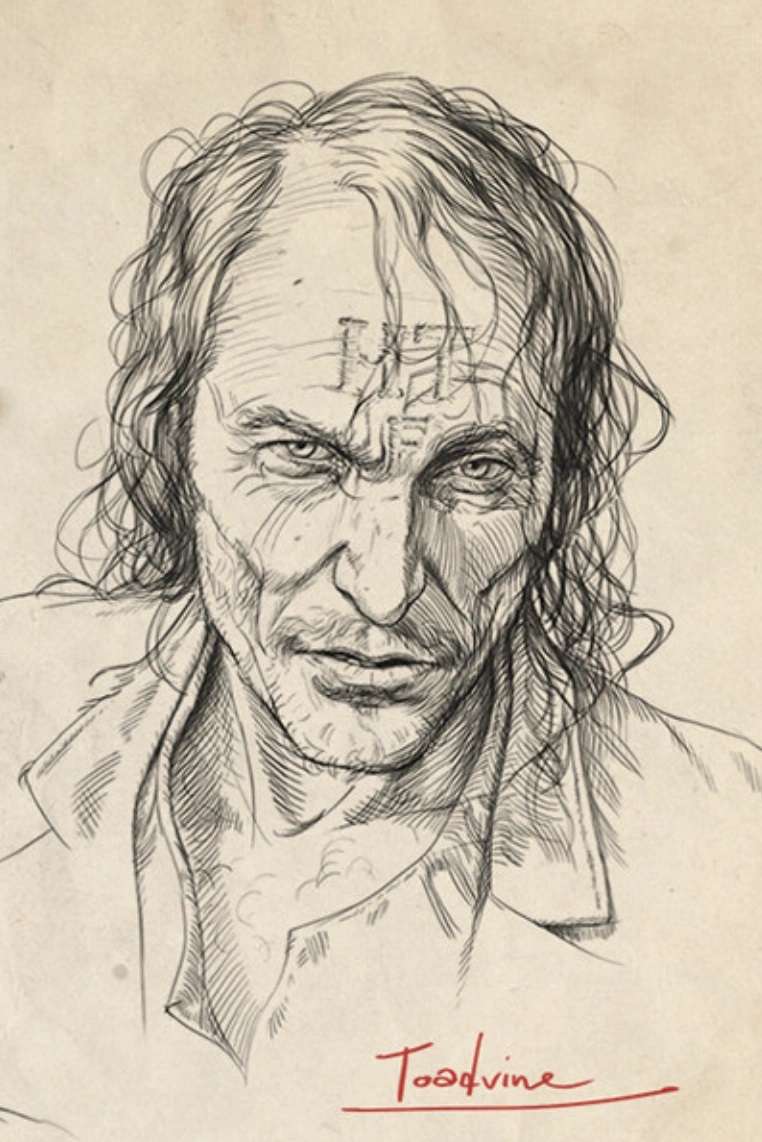

| Louis Toadvine | A branded fugitive, Toadvine first appears in Nacogdoches, Texas, where he almost murders the kid after a petty altercation, though they soon become compatriots and burn down a hotel together. The two find themselves in one another's company again while imprisoned in Chihuahua City along with Grannyrat. Toadvine secures their freedom by enlisting them all in Glanton's gang of scalp hunters. Toadvine is a somewhat complex character: he is a capricious murderer who goes so far as to kill a prison overseer and macabrely fashion his golden teeth into a necklace, yet he nonetheless violently objects when the Judge plays with, only to slaughter and scalp, an Apache infant. Some time after the Yuma massacre on the Colorado River and its aftermath, Toadvine, along with David Brown, is executed by hanging in Los Angeles. |

| David Brown | Often called Davy Brown, an especially violent deputy in Glanton's gang and Charlie Brown's brother; he comes to wear a necklace of human ears, perhaps recovered from Bathcat's corpse. When the gang first came upon the Judge in the desert, David Brown wanted to leave him but was overruled. Brown later dismisses the Judge's lecture on order and purpose in the universe as "craziness," and calls the Judge crazy again when the giant declares that war is God. In San Diego, Brown is jailed for lighting a soldier on fire with his cigar but bribes one of his jailers to free him, only to murder the jailer and take his ears to add to his necklace. Thereafter he seems intent on defecting from Glanton's gang. Some time after the Yuma massacre on the Colorado River and its aftermath, Brown, along with Toadvine, is executed by hanging in Los Angeles. The kid buys the dead Brown's necklace of ears for two dollars. |

| Ben Tobin | A member of Glanton's gang, Tobin is often called the ex-priest, but he later tells the Judge that he was merely "a novitiate to the order." To some extent, he and the Judge compete with one another for spiritual influence over the kid. Indeed, after the Yuma massacre Tobin and the kid informally ally themselves against the Judge while all of them are destitute in the desert—but though Tobin repeatedly tells the kid that he must kill the Judge, the kid declines for whatever reason to do so. Shot by the Judge while bearing a makeshift cross, Tobin nonetheless escapes with the kid to San Diego where he seeks medical attention. His fate is unknown. |

| The John Jacksons | Two members of Glanton's gang are named John Jackson, one white, the other black. Bathcat bets that the black will kill the white, which does indeed come to pass when the white drives the black away from a campfire around which are seated only white men. Although the family of magicians foretells that the black Jackson can begin his life anew and change his fate—and despite a failed attempt to desert the gang—the black Jackson stays the course of ruthless violence. He murders the proprietor of an eating-house in Tucson, Owens, and seems to have become something of a disciple of the Judge toward the end of his life, even imitating the Judge's garb, "a mantle of freeflowing cloth." The black Jackson is killed by the Yumas who raid the gang's ferry and nearby fortifications on the Colorado River. |

| Grannyrat Chambers | A Kentuckian whom the kid meets while the two are incarcerated, along with Toadvine, in the prison in Chihuahua City, Grannyrat served in the Mexico-American War and was part of the force that sacked Chihuahua City during that conflict. Grannyrat joins Glanton's gang, only to disappear from the gang soon after arriving in Janos. He is probably murdered by the Delawares as a deserter. |

| Bathcat | A native of Wales, Bathcat later traveled to Van Diemen's Land (present-day Tasmania) to hunt aborigines; he wears a necklace of human ears. Like Toadvine, he is a fugitive from the law. During the gang's flight from General Elias's army, Bathcat is sent out as a scout, never to return. He is found along with the other scouts days later dead and hideously mutilated, hanging from a tree. |

| The Delawares | Native American members of Glanton's gang who often serve as scouts. One is carried off by a bear in the mountains. Two other Delawares are seriously wounded while the gang is fleeing from General Elias's army, and a third kills them so that they are spared a more torturous fate at Elias's hands. |

| Juan "McGill" Miguel | The only Mexican member of Glanton's gang, called McGill throughout the novel, an American mispronunciation of his name. McGill takes an old Apache woman's scalp in Janos. When McGill is lanced during the gang's massacre of the Gileños Indians, the kid attempts to help him, but Glanton orders him not to and shoots McGill in the head. The gang then takes McGill's scalp because they might as well profit from it. |

| Frank Carroll | Runs the bodega that Glanton and his men drink in while staying in the town of Jesús María. After townspeople burn down his bodega, Carroll along with a man named Sanford, leaves town to join Glanton's gang. However, by the time the gang reaches Ures, the capital of the Mexican state of Sonora, both Carroll and Sanford have deserted. |

| Sam Tate | A member of Glanton's gang, from Kentucky. Along with Tobin and other gang members, Tate served with McCulloch's Rangers during the Mexican-American War. He is assigned by lottery to kill one of the four men wounded by General Elias's army, but the kid excuses him from this bad duty. While trying to catch up with Glanton's gang, the kid and Tate are ambushed by five of Elias's scouts. The kid escapes, but Tate is probably captured and worse. |

| Dick Shelby | A member of Glanton's gang, Shelby is wounded during a skirmish with General Elias's army and Glanton orders that he be killed. Although assigned by lottery to do the killing, the kid spares Shelby's life and accommodates his wish to be hidden under a bush; even after Shelby attempts to steal his pistol, the kid gives him water from his own canteen. Shelby is probably captured and worse by Elias's army. |

| Doc Irving | A member of Glanton's gang and presumably a medical doctor at one time, Irving refuses to help David Brown when he takes an arrow to the thigh, knowing that if he doesn't get the arrow out cleanly Brown will kill him. He also claims, in disagreement with the Judge, that might doesn't make right. |

| Captain White | The racist leader of an army of filibusters—government soldiers operating outside the limits of the law—with which the kid rides and a staunch advocate for American imperialism, White is embittered by the aftermath of the Mexican-American War and becomes hell-bent on invading and seizing Mexican territory. He claims to be an American patriot, yet he hypocritically breaks American law in invading Mexico. He claims to be delivering justice and liberation to "a dark and troubled land," yet he hypocritically plans on pillaging the country of its resources. White survives the Comanches' destruction of his army, but dies at the hands of Mexican bandits. The last the kid sees of Captain White is his head floating in a jar of mescal. |

| Sergeant Trammel | A sergeant in Captain White's army of filibusters, Trammel seeks out on the Captain's orders the man who so brutally attacked a bartender in Bexar, Texas. That attacker turns out to be the kid. After Trammel promises the kid that joining the filibusters will raise him in the world, the kid agrees to interview with Captain White. Trammel probably dies when the Comanches massacre White's army. |

| Sproule | A member of Captain White’s army, Sproule is, along with the kid, one of the few survivors of the massacre inflicted by the Comanches on White’s army. Though wounded in the arm, Sproule manages to trek through the desert alongside the kid. The two encounter merciful Mexican bandits, but one night Sproule is attacked by a vampire bat. He dies in a wagon en route to an unnamed Mexican town, and the kid is arrested by Mexican soldiers soon after. |

| Angel Trias | The Governor of Chihuahua, Trias was sent abroad for his education as a young man and is well read in the Classics, second in erudition only to the Judge, with whom he converses at length during a banquet held in the scalp hunters’ honor. Trias contracts Glanton’s gang to hunt the warlike and despotic Apaches in Sonora, and to pay the men for each Apache scalp they return with. However, when the scalp hunters begin slaughtering Mexican citizens, Trias rescinds the contract and places a bounty on Glanton’s head. |

| Sergeant Aguilar | A Mexican sergeant, Aguilar and his men investigate when Glanton creates a disturbance while testing the revolvers delivered by Speyer. The Judge warmly introduces Aguilar to each of the gang members and explains how one of the just-delivered revolvers works. After receiving some money and a handshake from the Judge, Sergeant Aguilar and his men ride off, leaving the scalp hunters to their business. |

| Colonel Garcia | The leader of a legion of one hundred Sonoran troops, on the hunt for a band of Apaches led by Pablo. Glanton exchanges rudimentary civilities with Garcia while leading his gang to California (though the gang as a unit never makes it farther than the ferry crossing on the Colorado River). |

| Reverend Green | Reverend Green, a representative of the Christian religion which is depicted as decaying in the novel, has set up a revival tent in Nacogdoches, Texas, sometime around the time of the kid’s arrival there. While an audience, including the kid, listens to the Reverend’s sermon against sinfulness, the Judge enters the tent and falsely accuses Green of child molestation and of having sexual intercourse with a goat. Outraged, members of Green’s congregation break out into violence and form a posse to hunt Green down. The Judge later reveals that he had never seen or heard of Green before in his life. |

| The hermit | While riding out of Nacogdoches, the kid comes upon a hovel belonging to the hermit, a man both filthy and half mad. The hermit accommodates the kid and his mule, going so far as to provide the kid with shelter during a stormy night. The hermit was once a slaver in Mississippi who keeps as a memento of those days a dried and blackened human heart. He tells the kid that whiskey, women, money, and black people have the power to destroy the world, and prophecies that human beings will create an evil that can sustain itself for a thousand years. |

| The Mennonite | A prophet whom the kid, Earl, and second corporal encounter while drinking in a bar in Bexar, the Mennonite warns the three men against joining Captain White on his undertaking, for he fears that White’s invasion of Mexico will wake the wrath of God. The kid and his companions berate the Mennonite and swear at him; but his prophecy comes true nonetheless. |

| The Family of Magicians |

A family consisting of an old man and a woman, as well as their son (called Casimero) and daughter. Each member of the family can do tricks, e.g., Casimero juggles dogs. Glanton’s gang escorts the family safely from the town of Corralitos to Janos. While camping in the night, the old man and woman read some of the gang members’ fortunes using Tarot cards; the woman foresees a calamitous end for Glanton, which does indeed come to pass. |

| The idiot | The intellectually and developmentally disabled brother of Cloyce Bell, kept in a filthy cage and treated like a freak-show attraction. His real name is James Robert Bell. The Judge rescues the fool from drowning in the Colorado River, and in the aftermath of the Yuma massacre leashes him like a dog, leading him along as the Judge pursues Tobin and the kid. The idiot’s fate is unknown. |

| Owens | The proprietor of an eating-house in Tucson. After Owens asks Glanton’s gang to move to a table reserved for "people of color" because of the presence of the black Jackson, David Brown pitches a gun to him and tells him to shoot the black Jackson. In turn, the black Jackson blows Owens’s brains out. |

| Doctor Lincoln | Owns and runs a ferry on the Colorado River, for which he charges a fee to cross. Glanton and the Judge later deceive Lincoln and appropriate the ferry for the gang’s purpose and profit, to Lincoln’s horror. He is killed and mutilated by the Yumas who later raid the ferry and nearby fortifications. |

| Elrod | A fifteen-year-old boy who works as a bonepicker on the plains of Texas. When the man tells Elrod and his companions how he came to be in possession of David Brown’s necklace of ears, Elrod accuses him of being a liar. Elrod returns to the man’s camp later that night armed with a rifle, and the man kills him. |

| Sloat | After falling ill and being left behind in Ures by his gold-seeking companions, Sloat joins Glanton’s gang. He dies soon thereafter, as a consequence of one of the gang’s skirmishes with General Elias’s army. |

| Earl | A Missourian and member of Captain White’s army, Earl goes out into Bexar with the kid and a second corporal for a night of drinking. That night Earl gets into drunken quarrels, and the next morning he is found dead in a courtyard. |

| General Zuloaga | A Mexican general and Conservative leader in the War of Reform, General Zuloaga receives Glanton, the Judge, and the brothers David and Charlie Brown at his hacienda outside of the town of Corralitos, where they all dine together and pass the night without incident. |

| Sarah Borginnis | A woman who, at Lincoln’s ferry crossing, shames Cloyce Bell for keeping his brother, the idiot, in a cage. She bathes the idiot in the Colorado River and orders that his cage be burnt. |

Your ideas are terrifying and your hearts are faint. Your acts of pity and cruelty are

absurd, committed with no calm, as if they were irresistible. Finally,

you fear blood

more and more. Blood and time.

PAUL VALERY

It is not to be thought that the life of darkness is sunk in misery and

lost as if in

sorrowing. There is no sorrowing. For sorrow is a thing that is swallowed

up in death,

and death and dying are the very life of the darkness.

JACOB BOEHME

Clark, who led last year's expedition to the Afar region of northern Ethiopia, and UC

Berkeley colleague Tim D. White, also said that a re-examination of a 3OO,000-year-old

fossil skull found in the same region earlier shows evidence of having been scalped.

THE YUMA DAILY SUN

June 13, 1982

I

Childhood in Tennessee-- Runs away-- New Orleans--

Fights-- Is shot-- To Galveston-- Nacogdoches--

The Reverend Green-- Judge Holden-- An affray-- Toadvine--

Burning of the hotel-- Escape.

See the child. He is pale and thin, he wears a thin and ragged linen shirt. He

stokes

the scullery fire. Outside lie dark turned fields with rags of snow and darker woods

beyond that harbor yet a few last wolves. His folk are known for hewers of wood and

drawers of water but in truth his father has been a schoolmaster. He lies in drink, he

quotes from poets whose names are now lost. The boy crouches by the fire and watches

him.

Night of your birth. Thirty-three. The Leonids they were called. God how the stars did

fall. I looked for blackness, holes in the heavens. The Dipper stove.

The mother dead these fourteen years did incubate in her own bosom the creature who

would carry her off. The father never speaks her name, the child does not know it. He

has a sister in this world that he will not see again. He watches, pale and unwashed.

He can neither read nor write and in him broods already a taste for mindless violence.

All history present in that visage, the child the father of the man.

At fourteen he runs away. He will not see again the freezing kitchenhouse in the

predawn dark. The firewood, the washpots. He wanders west as far as Memphis, a

solitary migrant upon that flat and pastoral landscape. Blacks in the fields, lank and

stooped, their fingers spiderlike among the bolls of cotton. A shadowed agony in the

garden. Against the sun's declining figures moving in the slower dusk across a paper

skyline. A lone dark husbandman pursuing mule and harrow down the rainblown

bottomland toward night.

A year later he is in Saint Louis. He is taken on for New Orleans aboard a flatboat.

Forty-two days on the river. At night the steamboats hoot and trudge past through the

black waters all alight like cities adrift. They break up the float and sell the lumber

and he walks in the streets and hears tongues he has not heard before. He lives in a

room above a courtyard behind a tavern and he comes down at night like some fairybook

beast to fight with the sailors. He is not big but he has big wrists, big hands. His

shoulders are set close. The child's face is curiously untouched behind the scars, the

eyes oddly innocent. They fight with fists, with feet, with bottles or knives. All races,

all breeds. Men whose speech sounds like the grunting of apes. Men from lands so far and

queer that standing over them where they lie bleeding in the mud he feels mankind

itself vindicated.

On a certain night a Maltese boatswain shoots him in the back with a small pistol.

Swinging to deal with the man he is shot again just below the heart. The man flees and

he leans against the bar with the blood running out of his shirt. The others look away.

After a while he sits in the floor.

He lies in a cot in the room upstairs for two weeks while the tavernkeeper's wife

attends him. She brings his meals, she carries out his slops. A hardlooking woman with

a wiry body like a man's. By the time he is mended he has no money to pay her and

he leaves in the night and sleeps on the riverbank until he can find a boat that will

take him on. The boat is going to Texas.

Only now is the child finally divested of all that he has been. His origins are become

remote as is his destiny and not again in all the world's turning will there be terrains

so wild and barbarous to try whether the stuff of creation may be shaped to man's will

or whether his own heart is not another kind of clay. The passengers are a diffident lot.

They cage their eyes and no man asks another what it is that brings him here. He sleeps

on the deck, a pilgrim among others. He watches the dim shore rise and fall. Gray sea-

birds gawking. Flights of pelicans coastwise above the gray swells.

They disembark aboard a lighter, settlers with their chattels, all studying the low

coastline, the thin bight of sand and scrub pine swimming in the haze.

He walks through the narrow streets of the port. The air smells of salt and newsawn

lumber. At night whores call to him from the dark like souls in want. A week and he is

on the move again, a few dollars in his purse that he's earned, walking the sand roads

of the southern night alone, his hands balled in the cotton pockets of his cheap coat.

Earthen causeways across the marshland. Egrets in their rookeries white as candles

among the moss. The wind has a raw edge to it and leaves lope by the roadside and

skelter on in the night fields. He moves north through small settlements and farms,

working for day wages and found. He sees a parricide hanged in a crossroads hamlet

and the man's friends run forward and pull his legs and he hangs dead from

his rope

while urine darkens his trousers.

He works in a sawmill, he works in a diptheria pesthouse. He takes as pay from a

farmer an aged mule and aback this animal in the spring of the year eighteen and

forty-nine he rides up through the latterday republic of Fredonia into the town of

Nacogdoches.

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

The Reverend Green had been playing to a full house daily as long as the rain had

been falling and the rain had been falling for two weeks. When the kid ducked into the

ratty canvas tent there was standing room along the walls, a place or two, and such a

heady reek of the wet and bathless that they themselves would sally forth into the

downpour now and again for fresh air before the rain drove them in again. He stood

with others of his kind along the back wall. The only thing that might have distin-

guished him in that crowd was that he was not armed.

Neighbors, said the reverend, he couldnt stay out of these here hell, hell, hellholes

right here in Nacogdoches. I said to him, said: You goin to take the son of God in there

with ye? And he said: Oh no. No I aint. And I said: Dont you know that he said I will

foller ye always even unto the end of the road?

Well, he said, I aint askin nobody to go nowheres. And I said: Neighbor, you dont need

to ask. He's a goin to be there with ye ever step of the way whether ye ask it or ye

dont. I said: Neighbor, you caint get shed of him. Now. Are you going to drag him,

him, into that hellhole yonder?

You ever see such a place for rain?

The kid had been watching the reverend. He turned to the man who spoke.

He wore

long moustaches after the fashion of teamsters and he wore a widebrim hat with a low

round crown. He was slightly walleyed and he was watching the kid earnestly as if he'd

know his opinion about the rain.

I just got here, said the kid.

Well it beats all I ever seen.

The kid nodded. An enormous man dressed in an oilcloth slicker had entered the tent

and removed his hat. He was bald as a stone and he had no trace of beard and he had

no brows to his eyes nor lashes to them. He was close on to seven feet in height and

he stood smoking a cigar even in this nomadic house of God and he seemed to have

removed his hat only to chase the rain from it for now he put it on again.

The reverend had stopped his sermon altogether. There was no sound in the

tent. All

watched the man. He adjusted the hat and then pushed his way forward as

far as the

crateboard pulpit where the reverend stood and there he turned to address the reve-

rend's congregation. His face was serene and strangely childlike. His hands were

small. He held them out.

Ladies and gentlemen I feel it my duty to inform you that the man holding this revival

is an imposter. He holds no papers of divinity from any institution recognized or

improvised. He is altogether devoid of the least qualification to the office he has

usurped and has only committed to memory a few passages from the good book for the

purpose of lending to his fraudulent sermons some faint flavor of the piety he despises.

In truth, the gentleman standing here before you posing as a minister of the Lord is not

only totally illiterate but is also wanted by the law in the states of Tennessee, Kentucky,

Mississippi, and Arkansas.

Oh God, cried the reverend. Lies, lies! He began reading feverishly from his opened

bible.

On a variety of charges the most recent of which involved a girl of eleven

years--I said

eleven--who had come to him in trust and whom he was surprised in the act

of violating

while actually clothed in the livery of his God.

A moan swept through the crowd. A lady sank to her knees.

This is him, cried the reverend, sobbing. This is him. The devil. Here he stands.

Let's hang the turd, called an ugly thug from the gallery to the rear.

Not three weeks before this he was run out of Fort Smith Arkansas for having congress

with a goat. Yes lady, that is what I said. Goat.

Why damn my eyes if I wont shoot the son of a bitch, said a man rising at the far side

of the tent, and drawing a pistol from his boot he leveled it and fired.

The young teamster instantly produced a knife from his cloth ng 춊 and unseamed the

tent and stepped outside into the rain. The kid followed. They ducked low and ran

across the mud toward the hotel. Already gunfire was general within the tent and a

dozen exits had been hacked through the canvas walls and people were pouring out,

women screaming, folk stumbling, folk trampled underfoot in the mud. The kid and his

friend reached the hotel gallery and wiped the water from their eyes and turned to

watch. As they did so the tent began to sway and buckle and like a huge and wounded

medusa it slowly settled to the ground trailing tattered canvas walls and ratty guy

ropes over the ground.

The baldheaded man was already at the bar when they entered.

On the polished wood before him were two hats and a double handful of coins. He

raised his glass but not to them. They stood up to the bar and ordered whiskeys and

the kid laid his money down but the barman pushed it back with his thumb and nodded.

These here is on the judge, he said.

They drank. The teamster set his glass down and looked at the kid or he seemed to,

you couldnt be sure of his gaze. The kid looked down the bar to where the judge stood.

The bar was that tall not every man could even get his elbows up on it but it came

just to the judge's waist and he stood with his hands placed flatwise on the wood,

leaning slightly, as if about to give another address. By now men were piling through

the doorway, bleeding, covered in mud, cursing. They gathered about the judge. A posse

was being drawn to pursue the preacher.

Judge, how did you come to have the goods on that no-account?

Goods? said the judge.

When was you in Fort Smith?

Fort Smith?

Where did you know him to know all that stuff on him?

You mean the Reverend Green?

Yessir. I reckon you was in Fort Smith fore ye come out here.

I was never in Fort Smith in my life. Doubt that he was.

They looked from one to the other.

Well where was it you run up on him?

I never laid eyes on the man before today. Never even heard of him.

He raised his glass and drank.

There was a strange silence in the room. The men looked like mud effigies. Finally

someone began to laugh. Then another. Soon they were all laughing together. Someone

bought the judge a drink.

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

It had been raining for sixteen days when he met Toadvine and it was raining yet. He

was still standing in the same saloon and he had drunk up all his money save two

dollars. The teamster had gone, the room was all but empty. The door stood open and

you could see the rain falling in the empty lot behind the hotel. He drained his glass

and went out. There were boards laid across the mud and he followed the paling band

of doorlight down toward the batboard jakes at the bottom of the lot. Another man was

coming up from the jakes and they met halfway on the narrow planks. The man before

him swayed slightly. His wet hatbrim fell to his shoulders save in the front where it

was pinned back. He held a bottle loosely in one hand. You better get out of my way, he

said.

The kid wasnt going to do that and he saw no use in discussing it. He kicked

the

man in the jaw. The man went down and got up again. He said: I'm goin to kill you.

He swung with the bottle and the kid ducked and he swung again and the kid stepped

back. When the kid hit him the man shattered the bottle against the side of his head.

He went off the boards into the mud and the man lunged after him with the jagged

bottleneck and tried to stick it in his eye. The kid was fending with his hands and they

were slick with blood. He kept trying to reach into his boot for his knife.

Kill your ass, the man said. They slogged about in the dark of the lot, coming out of

their boots. The kid had his knife now and they circled crabwise and when the man

lurched at him he cut the man's shirt open. The man threw down the bottleneck and

unsheathed an immense bowieknife from behind his neck. His hat had come off and his

black and ropy locks swung about his head and he had codified his threats to the one

word kill like a crazed chant.

That'ns cut, said one of several men standing along the walkway watching.

Kill kill slobbered the man wading forward.

But someone else was coming down the lot, great steady sucking sounds like

a cow.

He was carrying a huge shellalegh. He reached the kid first and when he swung with

the club the kid went face down in the mud. He'd have died if someone hadn't turned

him over.

When he woke it was daylight and the rain had stopped and he was looking up into the

face of a man with long hair who was completely covered in mud. The man was saying

something to him.

What? said the kid.

I said are you quits?

Quits?

Quits. Cause if you want some more of me you sure as hell goin to get it.

He looked at the sky. Very high, very small, a buzzard. He looked at the man. Is my

neck broke? he said.

The man looked out over the lot and spat and looked at the boy again. Can you not get

up?

I dont know. I aint tried.

I never meant to break your neck.

No.

I meant to kill ye.

They aint nobody done it yet. He clawed at the mud and pushed himself up. The man

was sitting on the planks with his boots alongside him. They aint nothin wrong with

you, he said.

The kid looked about stiffly at the day. Where's my boots? he said.

The man squinted at him. Flakes of dried mud fell from his face.

I'm goin to have to kill some son of a bitch if they got my boots.

Yonder looks like one of em.

The kid labored off through the mud and fetched up one boot. He slogged about in the

yard feeling likely lumps of mud.

This your knife? he said.

The man squinted at him. Looks like it, he said.

The kid pitched it to him and he bent and picked it up and wiped the huge blade on

his trouserleg. Thought somebody'd done stole you, he told the knife.

The kid found his other boot and came and sat on the boards. His hands were huge

with mud and he wiped one of them briefly at his knee and let it fall again.

They sat there side by side looking out across the barren lot. There was a picket

fence at the edge of the lot and beyond the fence a boy was drawing water at a well

and there were chickens in the yard there. A man came from the dramshop door down

the walk toward the outhouse. He stopped where they sat and looked at them and then

stepped off into the mud. After a while he came back and stepped off into the mud

again and went around and on up the walk.

The kid looked at the man. His head was strangely narrow and his hair was plastered

up with mud in a bizarre and primitive coiffure. On his forehead were burned the

letters H T and lower and almost between the eyes the letter F and these markings

were splayed and garish as if the iron had been left too long. When he

turned to look

at the kid the kid could see that he had no ears. He stood up and sheathed the knife

and started up the walk with the boots in his hand and the kid rose and followed.

Halfway to the hotel the man stopped and looked out at the mud and then sat down

on the planks and pulled on the boots mud and all. Then he rose and slogged off

through the lot to pick something up.

I want you to look here, he said. At my goddamned hat.

You couldnt tell what it was, something dead. He flapped it about and pulled it over his

head and went on and the kid followed.

The dramhouse was a long narrow hall wainscotted with varnished boards. There were

tables by the wall and spittoons on the floor. There were no patrons. The barman

looked up when they entered and a nigger that had been sweeping the floor stood the

broom against the wall and went out.

Where's Sidney? said the man in his suit of mud.

In the bed I reckon.

They went on.

Toadvine, called the barman.

The kid looked back.

The barman had come from behind the bar and was looking after them. They crossed

from the door through the lobby of the hotel toward the stairs leaving varied forms of

mud behind them on the floor. As they started up the stairs the clerk at the desk

leaned and called to them.

Toadvine.

He stopped and looked back.

He'll shoot you.

Old Sidney?

Old Sidney.

They went on up the stairs.

At the top of the landing was a long hall with a windowlight at the end. There were

varnished doors down the walls set so close they might have been closets. Toadvine

went on until he came to the end of the hall. He listened at the last door and he eyed

the kid.

You got a match?

The kid searched his pockets and came up with a crushed and stained wooden box.

The man took it from him. Need a little tinder here, he said. He was crumbling the box

and stacking the bits against the door. He struck a match and set the pieces alight. He

pushed the little pile of burning wood under the door and added more matches.

Is he in there? said the boy.

That's what we're fixin to see.

A dark curl of smoke rose, a blue flame of burning varnish. They squatted in the

hallway and watched. Thin flames began to run up over the panels and dart back again.

The watchers looked like forms excavated from a bog.

Tap on the door now, said Toadvine.

The kid rose. Toadvine stood up and waited. They could hear the flames crackling inside

the room. The kid tapped.

You better tap louder than that. This man drinks some.

He balled his fist and lambasted the door about five times.

Hell fire, said a voice.

Here he comes.

They waited.

You hot son of a bitch, said the voice. Then the knob turned and the door opened.

He stood in his underwear holding in one hand the towel he'd used to turn the

doorknob with. When he saw them he turned and started back into the room but

Toadvine seized him about the neck and rode him to the floor and held him by the hair

and began to pry out an eyeball with his thumb. The man grabbed his wrist and bit it.

Kick his mouth in, called Toadvine. Kick it.

The kid stepped past them into the room and turned and kicked the man in the face.

Toadvine held his head back by the hair.

Kick him, he called. Aw, kick him, honey.

He kicked.

Toadvine pulled the bloody head around and looked at it and let it flop to the floor and

he rose and kicked the man himself. Two spectators were standing in the hallway. The

door was com letely afire and part of the wall and ceiling. They went out and down

the hall. The clerk was coming up the steps two at a time.

Toadvine you son of a bitch, he said.

Toadvine was four steps above him and when he kicked him he caught him in the

throat. The clerk sat down on the stairs. When the kid came past he hit him in the

side of the head and the clerk slumped over and began to slide toward the

landing. The

kid stepped over him and went down to the lobby and crossed to the front door and

out.

Toadvine was running down the street, waving his fists above his head crazily and

laughing. He looked like a great clay voodoo doll made animate and the kid looked like

another. Behind them flames were licking at the top corner of the hotel and clouds of

dark smoke rose into the warm Texas morning.

He'd left the mule with a Mexican family that boarded animals at the edge of town and

he arrived there wildlooking and out of breath. The woman opened the door and looked

at him.

Need to get my mule, he wheezed.

She looked at him some more, then she called toward the back of the house. He walked

around. There were horses tethered in the lot and there was a flatbed wagon against the

fence with some turkeys sitting on the edge looking out. The old lady had come to the

back door. Nito, she called. Venga. Hay un caballero aquf. Venga.

He went down the shed to the tackroom and got his wretched saddle and his blanketroll

and brought them back. He found the mule and unstalled it and bridled it with the

rawhide hackamore and led it to the fence. He leaned against the animal

with his

shoulder and got the saddle over it and got it cinched, the mule starting and shying and

running its head along the fence. He led it across the lot. The mule kept shaking its

head sideways as if it had something in its ear.

He led it out to the road. As he passed the house the woman came padding out after

him. When she saw him put his foot in the stirrup she began to run. He swung up into

the broken saddle and chucked the mule forward. She stopped at the gate and watched

him go. He didnt look back.

When he passed back through the town the hotel was burning and men were standing

around watching it, some holding empty buckets. A few men sat horseback watching the

flames and one of these was the judge. As the kid rode past the judge turned and

watched him. He turned the horse, as if he'd have the animal watch too. When the kid

looked back the judge smiled. The kid touched up the mule and they went sucking out

past the old stone fort along the road west.

II

Across the prairie-- A hermit-- A nigger's heart--

A stormy night-- Westward again-- Cattle drovers-- Their kindness--

On the trail again-- The deadcart-- San Antonio de Bexar--

A Mexican cantina-- Another fight-- The abandoned church--

The dead in the sacristy-- At the ford-- Bathing in the river.

Now come days of begging, days of theft. Days of riding where there rode no

soul save

he. He's left behind the pinewood country and the evening sun declines

before him be-

yond an endless swale and dark falls here like a thunderclap and a cold

wind sets the

weeds to gnashing. The night sky lies so sprent with stars that there is scarcely space of

black at all and they fall all night in bitter arcs and it is so that their numbers are no

less.

He keeps from off the king's road for fear of citizenry. The little prairie wolves cry all

night and dawn finds him in a grassy draw where he'd gone to hide from the wind. The

hobbled mule stands over him and watches the east for light.

The sun that rises is the color of steel. His mounted shadow falls for miles before him.

He wears on his head a hat he's made from leaves and they have dried and cracked in

the sun and he looks like a raggedyman wandered from some garden where he'd used

to frighten birds.

Come evening he tracks a spire of smoke rising oblique from among the low hills and

before dark he hails up at the doorway of an old anchorite nested away in the sod like

a groundsloth. Solitary, half mad, his eyes redrimmed as if locked in their cages with

hot wires. But a ponderable body for that. He watched wordless while the kid eased

down stiffly from the mule. A rough wind was blowing and his rags flapped about him.

Seen ye smoke, said the kid. Thought you might spare a man a sup of water.

The old hermit scratched in his filthy hair and looked at the ground. He turned and

entered the hut and the kid followed.

Inside darkness and a smell of earth. A small fire burned on the dirt floor and the only

furnishings were a pile of hides in one corner. The old man shuffled through the gloom,

his head bent to clear the low ceiling of woven limbs and mud. He pointed down to

where a bucket stood in the dirt. The kid bent and took up the gourd floating there and

dipped and drank. The water was salty, sulphurous. He drank on.

You reckon I could water my old mule out there?

The old man began to beat his palm with one fist and dart his eyes about.

Be proud to fetch in some fresh. Just tell me where it's at.

What ye aim to water him with?

The kid looked at the bucket and he looked around in the dim hut.

I aint drinkin after no mule, said the hermit.

Have you not got no old bucket nor nothin?

No, cried the hermit. No. I aint. He was clapping the heels of his clenched fists together

at his chest.

The kid rose and looked toward the door. Ill find somethin, he said. Where's the well

at?

Up the hill, foller the path.

It's nigh too dark to see out here.

It's a deep path. Foller ye feet. Foller ye mule. I caint go.

He stepped out into the wind and looked about for the mule but the mule wasnt there.

Far to the south lightning flared soundlessly. He went up the path among

the thrashing

weeds and found the mule standing at the well.

A hole in the sand with rocks piled about it. A piece of dry hide for a cover and a

stone to weight it down. There was a rawhide bucket with a rawhide bail

and a rope of

greasy leather. The bucket had a rock tied to the bail to help it tip and fill and he

lowered it until the rope in his hand went slack while the mule watched over his

shoulder.

He drew up three bucketfuls and held them so the mule would not spill them and then

he put the cover back over the well and led the mule back down the path to the hut.

I thank ye for the water, he called.

The hermit appeared darkly in the door. Just stay with me, he said.

That's all right.

Best stay. It's fixin to storm.

You reckon?

I reckon and I reckon right.

Well.

Bring ye bed. Bring ye possibles.

He uncinched and threw down the saddle and hobbled the mule foreleg to rear and

took his bedroll in. There was no light save the fire and the old man was squatting by

it tailorwise.

Anywheres, anywheres, he said. Where's ye saddle at?

The kid gestured with his chin.

Dont leave it out yonder somethinll eat it. This is a hungry country.

He went out and ran into the mule in the dark. It had been standing looking in at the

fire.

Get away, fool, he said. He took up the saddle and went back in.

Now pull that door to fore we blow away, said the old man.

The door was a mass of planks on leather hinges. He dragged it across the dirt and

fastened it by its leather latch.

I take it ye lost your way, said the hermit.

No, I went right to it.

He waved quickly with his hand, the old man. No, no, he said. I mean ye was lost to

of come here. Was they a sandstorm? Did ye drift off the road in the night? Did thieves

beset ye?

The kid pondered this. Yes, he said We got off the road someways or another.

Knowed ye did.

How long you been out here?

Out where?

The kid was sitting on his blanketroll across the fire from the old man. Here, he said.

In this place.

The old man didnt answer. He turned his head suddenly aside and seized his nose

between his thumb and forefinger and blew twin strings of snot onto the floor and

wiped his fingers on the seam of his jeans. I come from Mississippi. I was a slaver,

dont care to tell it. Made good money. I never did get caught. Just got sick of it. Sick

of niggers. Wait till I show ye somethin.

He turned and rummaged among the hides and handed through the flames a small dark

thing. The kid turned it in his hand. Some man's heart, dried and blackened. He passed

it back and the old man cradled it in his palm as if he'd weigh it.

They is four things that can destroy the earth, he said. Women, whiskey, money, and

niggers.

They sat in silence. The wind moaned in the section of stovepipe that was run through

the roof above them to quit the place of smoke. After a while the old man put the

heart away.

That thing costed me two hundred dollars, he said.

You give two hundred dollars for it?

I did, for that was the price they put on the black son of a bitch it hung inside of.

He stirred about in the corner and came up with an old dark brass kettle, lifted the

cover and poked inside with one finger. The remains of one of the lank prairie hares

interred in cold grease and furred with a light blue mold. He clamped the lid back on

the kettle and set it in the flames. Aint much but we'll go shares, he said.

I thank ye.

Lost ye way in the dark, said the old man. He stirred the fire, standing slender tusks of

bone up out of the ashes.

The kid didnt answer.

The old man swung his head back and forth. The way of the transgressor is hard. God

made this world, but he didnt make it to suit everbody, did he?

I dont believe he much had me in mind.

Aye, said the old man. But where does a man come by his notions. What world's he

seen that he liked better?

I can think of better places and better ways.

Can ye make it be?

No.

No. It's a mystery. A man's at odds to know his mind cause his mind is aught he has

to know it with. He can know his heart, but he dont want to. Rightly so. Best not to

look in there. It aint the heart of a creature that is bound in the way that God has set

for it. You can find meanness in the least of creatures, but when God made man the

devil was at his elbow. A creature that can do anything. Make a machine. And a machine

to make the machine. And evil that can run itself a thousand years, no need to tend

it. You believe that?

I dont know.

Believe that.

When the old man's mess was warmed he doled it out and they ate in silence. Thunder

was moving north and before long it was booming overhead and starting bits of rust in

a thin trickle down the stovepipe. They hunkered over their plates and wiped the grease

up with their fingers and drank from the gourd.

The kid went out and scoured his cup and plate in the sand and came back banging

the tins together as if to fend away some drygulch phantom out there in the dark.

Distant thunderheads reared quivering against the electric sky and were sucked away in

the blackness again. The old man sat with one ear cocked to the howling waste without.

The kid shut the door.

Dont have no bacca with ye do ye?

No I aint, said the kid.

Didnt allow ye did.

You reckon it'll rain?

It's got ever opportunity. Likely it wont.

The kid watched the fire. Already he was nodding. Finally he raised up and shook his

head. The hermit watched him over the dying flames. Just go on and fix ye bed, he

said.

He did. Spreading his blankets on the packed mud and pulling off his stinking boots.

The fluepipe moaned and he heard the mule stamp and snuffle outside and in his sleep

he struggled and muttered like a dreaming dog.

He woke sometime in the night with the hut in almost total darkness and the hermit

bent over him and all but in his bed.

What do you want? he said. But the hermit crawled away and in the morning when he

woke the hut was empty and he got his things and left.

All that day he watched to the north a thin line of dust. It seemed not to move at

all and it was late evening before he could see that it was headed his way. He passed

through a forest of live oak and he watered at a stream and moved on in the dusk and

made a fireless camp. Birds woke him where he lay in a dry and dusty wood.

By noon he was on the prairie again and the dust to the north was stretched out along

the edge of the earth. By evening the first of a drove of cattle came into view. Rangy

vicious beasts with enormous hornspreads. That night he sat in the herders' camp and

ate beans and pilotbread and heard of life on the trail.

They were coming down from Abilene, forty days out, headed for the markets in Louisiana.

Followed by packs of wolves, coyotes, indians. Cattle groaned about them for miles in

the dark.

They asked him no questions, a ragged lot themselves. Cross reeds some, free niggers,

an indian or two.

I had my outfit stole, he said.

They nodded in the firelight.

They got everthing I had. I aint even got a knife.

You might could sign on with us. We lost two men. Turned back to go to Californy.

I'm headed yon way.

I guess you might be goin to Californy ye own self.

I might. I aint decided.

Them boys was with us fell in with a bunch from Arkansas. They was headed down for

Bexar. Goin to pull for Mexico and the west.

I'll bet them old boys is in Bexar drinkin they brains out.

I'll bet old Lonnie's done topped ever whore in town.

How far is it to Bexar?

It's about two days.

It's furthern that. More like four I'd say.

How would a man go if he'd a mind to?

You cut straight south you ought to hit the road about half a day.

You going to Bexar?

I might do.

You see old Lonnie down there you tell him get a piece for me. Tell him old Oren.

He'll buy ye a drink if he aint blowed all his money in.

In the morning they ate flapjacks with molasses and the herders saddled up and moved

on. When he found his mule there was a small fibre bag tied to the animal's rope and

inside the bag there was a cupful of dried beans and some peppers and an old green-

river knife with a handle made of string. He saddled up the mule, the mule's back

galled and balding, the hooves cracked. The ribs like fishbones. They hobbled on

across the endless plain.

He came upon Bexar in the evening of the fourth day and he sat the tattered mule on

a low rise and looked down at the town, the quiet adobe houses, the line of green oaks

and cottonwoods that marked the course of the river, the plaza filled with wagons with

their osnaburg covers and the whitewashed public buildings and the Moorish churchdome

rising from the trees and the garrison and the tall stone powderhouse in the distance.

A light breeze stirred the fronds of his hat, his matted greasy hair. His eyes lay

dark and tunneled in a caved and haunted face and a foul stench rose from the wells

of his boot tops. The sun was just down and to the west lay reefs of bloodred clouds

up out of which rose little desert nighthawks like fugitives from some great fire

at the earth's end. He spat a dry white spit and clumped the cracked wooden stirrups

against the mule's ribs and they staggered into motion again.

He went down a narrow sandy road and as he went he met a deadcart bound out with

a load of corpses, a small bell tolling the way and a lantern swinging from the gate.

Three men sat on the box not unlike the dead themselves or spirit folk so white they

were with lime and nearly phosphorescent in the dusk. A pair of horses drew the cart

and they went on up the road in a faint miasma of carbolic and passed from sight. He

turned and watched them go. The naked feet of the dead jostled stiffly from side to

side.

It was dark when he entered the town, attended by barking dogs, faces parting the

curtains in the lamplit windows. The light clatter of the mule's hooves echoing in the

little empty streets. The mule sniffed the air and swung down an alleyway into a square

where there stood in the starlight a well, a trough, a hitchingrail. The kid eased himself

down and took the bucket from the stone coping and lowered it into the well. A light

splash echoed. He drew the bucket, water dripping in the dark. He dipped the gourd

and drank and the mule nuzzled his elbow. When he'd done he set the bucket in the

street and sat on the coping of the well and watched the mule drink from the bucket.

He went on through the town leading the animal. There was no one about. By and by

he entered a plaza and he could hear guitars and a horn. At the far end of the square

there were lights from a cafe and laughter and highpitched cries. He led the mule into

the square and up the far side past a long portico toward the lights.

There was a team of dancers in the street and they wore gaudy costumes and called out

in Spanish. He and the mule stood at the edge of the lights and watched. Old men sat

along the tavern wall and children played in the dust. They wore strange costumes all,

the men in dark flatcrowned hats, white nightshirts, trousers that buttoned up the

outside leg and the girls with garish painted faces and tortoiseshell combs in their

blueblack hair. The kid crossed the street with the mule and tied it and entered the

cafe. A number of men were standing at the bar and they quit talking when he entered.

He crossed the polished clay floor past a sleeping dog that opened one eye and looked

at him and he stood at the bar and placed both hands on the tiles. The barman nodded

to him. Digame, he said.

I aint got no money but I need a drink. I'll fetch out the slops or mop the floor or

whatever.

The barman looked across the room to where two men were playing dominoes at a

table. Abuelito, he said.

The older of the two raised his head.

Que dice el muchacho.

The old man looked at the kid and turned back to his dominoes.

The barman shrugged his shoulders.

The kid turned to the old man. You speak american? he said.

The old man looked up from his play. He regarded the kid without expression.

Tell him I'll work for a drink. I aint got no money.

The old man thrust his chin and made a clucking noise with his tongue.

The kid looked at the barman.

The old man made a fist with the thumb pointing up and the little finger down and

tilted his head back and tipped a phantom drink down his throat. Quiere

hecharse una

copa, he said. Pero no puede pagar.

The men at the bar watched.

The barman looked at the kid.

Quiere trabajo, said the old man. Quien sabe. He turned back to his pieces and made

his play without further consultation.

Quieres trabajar, said one of the men at the bar.

They began to laugh.

What are you laughing at? said the boy.

They stopped. Some looked at him, some pursed their mouths or shrugged. The boy

turned to the bartender. You got something I could do for a couple of drinks I know

damn good and well.

One of the men at the bar said something in Spanish. The boy glared at them. They

winked one to the other, they took up their glasses.

He turned to the barman again. His eyes were dark and narrow. Sweep the floor, he

said.

The barman blinked.

The kid stepped back and made sweeping motions, a pantomime that bent the

drinkers

in silent mirth. Sweep, he said, pointing at the floor.

No esta sucio, said the barman.

He swept again. Sweep, goddamnit, he said.

The barman shrugged. He went to the end of the bar and got a broom and brought it

back. The boy took it and went on to the back of the room.

A great hall of a place. He swept in the corners where potted trees stood silent in the

dark. He swept around the spittoons and he swept around the players at the table and

he swept around the dog. He swept along the front of the bar and when he reached the

place where the drinkers stood he straightened up and leaned on the broom and looked

at them. They conferred silently among themselves and at last one took his glass from

the bar and stepped away. The others followed. The kid swept past them to the door.

The dancers had gone, the music. Across the street sat a man on a bench dimly lit in

the doorlight from the cafe. The mule stood where he'd tied it. He tapped the broom on

the steps and came back in and took the broom to the corner where the barman had

gotten it. Then he came to the bar and stood.

The barman ignored him.

The kid rapped with his knuckles.

The barman turned and put one hand on his hip and pursed his lips.

How about that drink now, said the kid.

The barman stood.

The kid made the drinking motions that the old man had made and the barman flapped

his towel idly at him.

Andale, he said. He made a shooing motion with the back of his hand.

The kid's face clouded. You son of a bitch, he said. He started down the bar. The

barman's expression did not change. He brought up from under the bar an oldfashioned

military pistol with a flint lock and shoved back the cock with the heel of his hand. A

great wooden clicking in the silence. A clicking of glasses all down the bar. Then the

scuffling of chairs pushed back by the players at the wall.

The kid froze. Old man, he said.

The old man didnt answer. There was no sound in the cafe. The kid turned to find him

with his eyes.

Esta borracho, said the old man.

The boy watched the barman's eyes.

The barman waved the pistol toward the door.

The old man spoke to the room in Spanish. Then he spoke to the barman. Then he put

on his hat and went out.

The barman's face drained. When he came around the end of the bar he had laid down

the pistol and he was carrying a bung-starter in one hand.

The kid backed to the center of the room and the barman labored over the floor toward

him like a man on his way to some chore. He swung twice at the kid and the kid

stepped twice to the right. Then he stepped backward. The barman froze. The kid

boosted himself lightly over the bar and picked up the pistol. No one moved.

He raked

the frizzen open against the bartop and dumped the priming out and laid the pistol

down again. Then he selected a pair of full bottles from the shelves behind him and

came around the end of the bar with one in each hand.

The barman stood in the center of the room. He was breathing heavily and he turned,

following the kid's movements. When the kid approached him he raised the bungstarter.

The kid crouched lightly with the bottles and feinted and then broke the right one over

the man's head. Blood and liquor sprayed and the man's knees buckled and his eyes

rolled. The kid had already let go the bottleneck and he pitched the second bottle into

his right hand in a roadagent's pass before it even reached the floor and he backhanded

the second bottle across the barman's skull and crammed the jagged remnant into his

eye as he went down.

The kid looked around the room. Some of those men wore pistols in their belts but

none moved. The kid vaulted the bar and took another bottle and tucked it under his

arm and walked out the door. The dog was gone. The man on the bench was gone too.

He untied the mule and led it across the square.

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

He woke in the nave of a ruinous church, blinking up at the vaulted ceiling and the

tall

swagged walls with their faded frescos. The floor of the church was deep in dried guano

and the droppings of cattle and sheep. Pigeons flapped through the piers of dusty light

and three buzzards hobbled about on the picked bone carcass of some animal dead in

the chancel.

His head was in torment and his tongue swollen with thirst. He sat up and looked

around him. He'd put the bottle under his saddle and he found it and held it up and

shook it and drew the cork and drank. He sat with his eyes closed, the sweat beaded

on his forehead. Then he opened his eyes and drank again. The buzzards stepped down

one by one and trotted off into the sacristy. After a while he rose and went out to

look for the mule.

It was nowhere in sight. The mission occupied eight or ten ares of enclosed land, a

barren purlieu that held a few goats and burros. In the mud walls of the enclosure were

cribs inhabited by families of squatters and a few cookfires smoked thinly in the sun.

He walked around the side of the church and entered the sacristy. Buzzards shuffled off

through the chaff and plaster like enormous yardfowl. The domed vaults overhead were

clotted with a dark furred mass that shifted and breathed and chittered. In the room

was a wooden table with a few clay pots and along the back wall lay the remains of

several bodies, one a child. He went on through the sacristy into the church again and

got his saddle. He drank the rest of the bottle and he put the saddle on his shoulder

and went out.

The facade of the building bore an array of saints in their niches and they had been

shot up by American troops trying their rifles, the figures shorn of ears and noses and

darkly mottled with leadmarks oxidized upon the stone. The huge carved and paneled

doors hung awap on their hinges and a carved stone Virgin held in her arms a headless

child. He stood blinking in the noon heat. Then he saw the mule's tracks. They

were

just the palest disturbance of the dust and they came out of the door of the church and

crossed the lot to the gate in the east wall. He hiked the saddle higher onto his

shoulder and set out after them.

A dog in the shade of the portal rose and lurched sullenly out into the sun until he

had passed and then lurched back. He took the road down the hill toward

the river, a

ragged figure enough. He entered a deep wood of pecan and oak and the road took a

rise and he could see the river below him. Blacks were washing a carriage in the ford

and he went down the hill and stood at the edge of the water and after a while he

called out to them.

They were sopping water over the black lacquerwork and one of them raised up and

turned to look at him. The horses stood to their knees in the current.

What? called the black.

Have you seen a mule.

Mule?

I lost a mule. I think he come this way.

The black wiped his face with the back of his arm. Somethin come down the road about

a hour back. I think it went down the river yonder. It might of been a mule. It didnt

have no tail nor no hair to speak of but it did have long ears.

The other two blacks grinned. The kid looked off down the river. He spat and set off

along the path through the willows and swales of grass.

He found it about a hundred yards downriver. It was wet to its belly and it looked up

at him and then lowered its head again into the lush river grass. He threw down the

saddle and took up the trailing rope and tied the animal to a limb and kicked it

halfheartedly. It shifted slightly to the side and continued to graze. He reached atop

his head but he had lost the crazy hat somewhere. He made his way down through the

trees and stood looking at the cold swirling waters. Then he waded out into the river

like some wholly wretched baptismal candidate.

III

Sought out to join an army-- Interview with Captain White--

His views-- The camp-- Trades his mule-- A cantina in the Laredito--

A Mennonite-- Companion killed.

He was lying naked under the trees with his rags spread across the limbs above him

when another rider going down the river reined up and stopped.

He turned his head. Through the willows he could see the legs of the horse. He rolled

over on his stomach.

The man got down and stood beside the horse.

He reached and got his twinehandled knife.

Howdy there, said the rider.

He didnt answer. He moved to the side to see better through, the branches.

Howdy there. Where ye at?

What do you want?

Wanted to talk to ye.

What about?

Hell fire, come on out. I'm white and Christian.

The kid was reaching up through the willows trying to get his breeches. The belt was

hanging down and he tugged at it but the breeches were hung on a limb.

Goddamn, said the man. You aint up in the tree are ye?

Why dont you go on and leave me the hell alone.

Just wanted to talk to ye. Didnt intend to get ye all riled up.

You done got me riled.

Was you the feller knocked in that Mexer's head yesterday evenin? I aint the law.

Who wants to know?

Captain White. He wants to sign that feller up to join the army.

The army?

Yessir.

What army?

Company under Captain White. We goin to whip up on the Mexicans.

The war's over.

He says it aint over. Where are you at?

He rose and hauled the breeches down from where he'd hung them and pulled them on.

He pulled on his boots and put the knife in the right bootleg and came out from the

willows pulling on his shirt.

The man was sitting in the grass with his legs crossed. He was dressed in buckskin and

he wore a plug hat of dusty black silk and he had a small Mexican cigar in the corner

of his teeth. When he saw what clawed its way out through the willows he shook his

head.

Kindly fell on hard times aint ye son? he said.

I just aint fell on no good ones.

You ready to go to Mexico?

I aint lost nothin down there.

It's a chance for ye to raise ye self in the world. You best make a move someway or

another fore ye go plumb in under.

What do they give ye?

Ever man gets a horse and his ammunition. I reckon we might find some clothes in

your case.

I aint got no rifle.

We'll find ye one.

What about wages?

Hell fire son, you wont need no wages. You get to keep ever-thing you can raise. We

goin to Mexico. Spoils of war. Aint a man in the company wont come out a big land-

owner. How much land you own now?

I dont know nothin about soldierin.

The man eyed him. He took the unlit cigar from his teeth and turned his head and spat

and put it back again. Where ye from? he said.

Tennessee.

Tennessee. Well I dont misdoubt but what you can shoot a rifle.

The kid squatted in the grass. He looked at the man's horse. The horse was fitted out

in tooled leather with worked silver trim. It had a white blaze on its face and four

white stockings and it was cropping up great teethfuls of the rich grass. Where you

from, said the kid.

I been in Texas since thirty-eight. If I'd not run up on Captain White I dont know

where I'd be this day. I was a sorrier sight even than what you are and he come along

and raised me up like Lazarus. Set my feet in the path of righteousness. I'd done took

to drinkin and whorin till hell wouldnt have me. He seen somethin in me worth savin

and I see it in you. What do ye say?

I dont know.

Just come with me and meet the captain.

The boy pulled at the halms of grass. He looked at the horse again. Well, he said. Dont

reckon it'd hurt nothin.

They rode through the town with the recruiter splendid on the stockingfooted horse

and the kid behind him on the mule like something he'd captured. They rode through

narrow lanes where the wattled huts steamed in the heat. Grass and prickly pear

grew on the roofs and goats walked about on them and somewhere off in that squalid

kingdom of mud the sound of the little deathbells tolled thinly. They turned up

Commerce Street through the Main Plaza among rafts of wagons and they crossed

another plaza where boys were selling grapes and figs from little trundlecarts.

A few bony dogs slank off before them. They rode through the Military Plaza and they

passed the little street where the boy and the mule had drunk the night before and

there were clusters of women and girls at the well and many shapes of wickercovered

clay jars standing about. They passed a little house where women inside were wailing

and the little hearsecart stood at the door with the horses patient and motionless

in the heat and the flies.

The captain kept quarters in a hotel on a plaza where there were trees and a small

green gazebo with benches. An iron gate at the hotel front opened into a passageway

with a courtyard at the rear. The walls were whitewashed and set with little ornate

colored tiles. The captain's man wore carved boots with tall heels that rang smartly

on the tiles and on the stairs ascending from the courtyard to the rooms above. In the

courtyard there were green plants growing and they were freshly watered

and steaming.

The captain's man strode down the long balcony and rapped sharply at the door at the

end. A voice said for them to come in.

He sat at a wickerwork desk writing letters, the captain. They stood attending, the

captain's man with his black hat in his hands. The captain wrote on nor did he look

up. Outside the kid could hear a woman speaking in Spanish. Other than that there was

just the scratching of the captain's pen.

When he had done he laid down the pen and looked up. He looked at his man and

then he looked at the kid and then he bent his head to read what he'd written. He

nodded to himself and dusted the letter with sand from a little onyx box and folded

it.Taking a match from a box of them on the desk he lit it and held it to a stick of

sealing wax until a small red medallion had pooled onto the paper. He shook out the

match, blew briefly at the paper and knuckled the seal with his ring. Then he stood the

letter between two books on his desk and leaned back in his chair and looked at the

kid again. He nodded gravely. Take seats, he said.

They eased themselves into a kind of settle made from some dark wood. The captain's

man had a large revolver at his belt and as he sat he hitched the belt around so that

the piece lay cradled between his thighs. He put his hat over it and leaned

back. The

kid folded his busted boots one behind the other and sat upright.

The captain pushed his chair back and rose and came around to the front of the desk.

He stood there for a measured minute and then he hitched himself up on the desk and

sat with his boots dangling. He had gray in his hair and in the sweeping moustaches

that he wore but he was not old. So you're the man, he said.

What man? said the kid.

What man sir, said the captain's man.

How old are you, son?

Nineteen.

The captain nodded his head. He was looking the kid over. What happened to you?

What?

Say sir, said the recruiter.

Sir?

I said what happened to you.

The kid looked at the man sitting next to him. He looked down at himself and he

looked at the captain again. I was fell on by robbers, he said.

Robbers, said the captain.

Took everthing I had. Took my watch and everthing.

Have you got a rifle?

Not no more I aint.

Where was it you were robbed.

I dont know. They wasnt no name to it. It was just a wilderness.

Where were you coming from?

I was comin from Naca, Naca ...

Nacogdoches?

Yeah.

Yessir.

Yessir.

How many were there?

The kid stared at him.

Robbers. How many robbers.

Seven or eight, I reckon. I got busted in the head with a scantlin.

The captain squinted one eye at him. Were they Mexicans?

Some. Mexicans and niggers. They was a white or two with em. They had a bunch of

cattle they'd stole. Only thing they left me with was a old piece of knife I had

in my boot.

The captain nodded. He folded his hands between his knees. What do you think of the

treaty? he said.

The kid looked at the man on the settle next to him. He had his eyes shut. He looked

down at his thumbs. I dont know nothin about it, he said.

I'm afraid that's the case with a lot of Americans, said the captain. Where are you from,

son?

Tennessee.

You werent with the Volunteers at Monterrey were you?

No sir.

Bravest bunch of men under fire I believe I ever saw. I suppose more men from

Ten-

nessee bled and died on the field in northern Mexico than from any other

state. Did

you know that?

No sir.

They were sold out. Fought and died down there in that desert and then they were sold

out by their own country.

The kid sat silent.

The captain leaned forward. We fought for it. Lost friends and brothers down there. And

then by God if we didnt give it back. Back to a bunch of barbarians that even the most

biased in their favor will admit have no least notion in God's earth of

honor or justice

or the meaning of republican government. A people so cowardly they've paid tribute a

hundred years to tribes of naked savages. Given up their crops and livestock. Mines shut

down. Whole villages abandoned. While a heathen horde rides over the land looting and

killing with total impunity. Not a hand raised against them. What kind of people are

these? The Apaches wont even shoot them. Did you know that? They kill them

with

rocks. The captain shook his head. He seemed made sad by what he had to

tell.

Did you know that when Colonel Doniphan took Chihuahua City he inflicted over a

thousand casualties on the enemy and lost only one man and him all but a suicide?

With an army of unpaid irregulars that called him Bill, were half naked, and had walked

to the battlefield from Missouri?

No sir.

The captain leaned back and folded his arms. What we are dealing with, he said, is a

race of degenerates. A mongrel race, little better than niggers. And maybe no better.

There is no government in Mexico. Hell, there's no God in Mexico. Never will be. We

are dealing with a people manifestly incapable of governing themselves. And do you

know what happens with people who cannot govern themselves? That's right. Others

come in to govern for them.

There are already some fourteen thousand French colonists in the state of Sonora.

They're being given free land to settle. They're being given tools and livestock.

Enlightened Mexicans encourage this. Paredes is already calling for secession from the

Mexican government. They'd rather be ruled by toadeaters than thieves and imbeciles.

Colonel Carrasco is asking for American intervention. And he's going to get it.

Right now they are forming in Washington a commission to come out here and draw up

the boundary lines between our country and Mexico. I dont think there's any question

that ultimately Sonora will become a United States territory. Guaymas a U S

port.

Americans will be able to get to California without having to pass through our benighted

sister republic and our citizens will be protected at last from the notorious packs of

cut throats presently infesting the routes which they are obliged to travel.

The captain was watching the kid. The kid looked uneasy. Son, said the captain. We are