COSETTE

BOOK FIRST

WATERLOO

I. WHAT YOU MEET IN COMING FROM LAVILLE

ON a beautiful morning in May, last year (1861), a traveller, hr who tells this story,

was journeying from Nivelles towarrds La Hulpe. He travelled a-foot. He was following,

between two rows of trees, a broad road, undulating over hills, which, one after another,

upheave it and let it fall again, like enormous waves. He has passed Lillois vand Bois-

Seigneur-lsaac. He saw to the west the slated steeple of Braine-l'Alleud,

which has the

form of an inverted vase. He had just passed a wood upon a hill, and at the corner of a

crossroad, beside a sort of worm-eaten sign-post, bearing the inscription --Old Toll-Gate,

No. 4--a tavern with this sign: The Four Winds. Echlaleau, Private Cafe.

Half a mile from this tavern, he reached the bottom of a little valley, where a stream flowed

beneath an arch in the embankment of the road. The cluster of trees, thin-sown but very

green, which fills the vale on one side of the road, on the other spreads into meadows,

and sweeps away in graceful disorder towards Braine l'Alleud.

At this point there was at the right. and immediately on the road, an inn, with a four-

wheeled cart before the door, a great bundle of hop-poles, a plough, a pile of dry brush

near a quickset hedge, some lime which was smoking in a square hole in the ground, and a

ladder lying along an old shed with mangers for straw. A young girl was pulling weeds in

a field. where a large green poster, probably of a travelling show at some annual fair,

fluttered in the wind. At the corner of the inn, beside a pond, in which a flotilla of

ducks was navigating, a difficult foot-path lost itself in the shrubbery.

The traveller

took this path.

At the end of a hundred paces, passing a wall of the fifteenth century, surmounted by a

sharp gable of crossed bricks, he found himself opposite a great arched stone doorway,

with rectilinear impost, in the solemn style of Louis XIV., and plain medallions on the

sides. Over the entrance wag a severe facade. and a wall perpendicular to the facade almost

touched the doorway. flanking it at an abrupt right angle. On the meadow before the door

by three harrows, through which were blooming, as best they could, all the

flowers of May.

The doorway was closed. It was shut by two decrepit folding-doors, decorated

with an old

rusty knocker.

The sunshine was enchanting; the branches of the trees had that gentle tremulousness of

the month of May which seems to come from the birds' nests rather than the wind. A spruce

little bird, ' probably in love, was singing desperately in a tall tree.

The traveller paused and examined in the stone at the left of the door, near the ground,

a large circular excavation like the hollow of a sphere. Just then the folding-doors open-

ed, and a peasant woman came out.

She saw the traveller, and perceived what he was examining. "It was a French ball which

did that," said she.

And she added--

"What you see there, higher up, in the door, near a nail, is the hole made by a Biscay

musket. The musket has not gone through the wood."

"What is the name of this place?" asked the traveller

"Hougomont," the woman answered.

The traveller raised his head. He took a few steps and looked over the

hedges. He saw in

the horizon, through the trees, a sort of hillock, and on this hillock something which,

in the distance, resembled a lion.

He was on the battle-field of Waterloo.

II. HOUGOMONT

Hougomoont--this was the fatal spot, the beginning of the resis-tance,

the first check

encountered at Waterloo by this great butcher of Europe, called Napoleon; the first knot

under the axe.

It was a chateau; it is now nothing more than a farm. Hougomont, to the antiquary, is

Hugomons. This manor was built by Hugo, sire de Somerel, the same who endowed the

sixth

chaplainship of the abbey of Villiers.

The traveller pushed open the door, elbowed an old carriage under the porch, and entered

the court.

The first thing that he noticed in this yard was a door of the sixteenth century, which

seemed like an arch, everything having fallen down around it. The monumental aspect is

often produced by ruin. Near the arch opens another door in the wall, with keystones of

the time of 'Henry IV., which discloses the trees of an orchard. Beside this door were a

dung-hill, mattocks and shovels, some carts, an old well with its flag-stone and iron

pulley, a skipping colt, a strutting turkey, a chapel surmounted by a little steeple, a

pear-tree in bloom, trained in espalier on the wall of the chapel; this

was the court,

the conquest of which was the aspiration of Napoleon. This bit of earth,

could he have

taken it, would perhaps have given him the world. The hens are scattering the dust with

their beaks. You hear a growling: it is a great dog, who shows his teeth,

and takes the

place of the English.

The English fought admirably there. The four companies of guards under Cooke held their

ground for seven hours, against the fury of an assaulting army.

Hougomont, seen on the map, on a geometrical plan, comprising buildings and inclosure,

presents a sort of irregular rectangle. one corner of which is cut off. At this corner

is the southern entrance, guarded by this wall, which commands it at the shortest musket

range. Hougomont has two entrances: the southern, that of the chateau, and the northern,

that of the farm. Napoleon sent against Hougomont his brother Jerome. The divisions of

Gunleminot. Foy, and Bachelu were hurled against it; nearly the whole corps of Reille

was there employed and there defeated, and the bullets of Kellermann were exhausted a-

gainst this heroic wall-front. It was too much for the brigade of Bauduin to force Hou-

gomont on the north, and the brigade of Soyc could only batter it on the south--it could

not take it.

The buildings of the farm are on the southern side of the court. A small portion of the

northern door, broken by the French, hangs dangling from the wall. It is composed of four

planks, nailed to two cross-pieces, and in it may be seen the scars of the attack.

The northern door, forced by the French, and to which a piece has been added to replace

the panel suspended from the wall, stands half open at the foot of the court-yard; it is

cut squarely in a wall of stone below, and brick above, and closes the court on the north.

It is a simple cart-door, such as are found on all small farms, composed of two large fold-

ing-doors, made of rustic planks; bevond this are the meadows. This entrance was furiously

contested. For a long time there could be seen upon the door all sorts

of prints of bloody

hands. It was there that Bauduin was killed.

The storm of the combat is still in this court: the horror is visible there; the overturn

of the conflict is there petrified; it lives, it dies; it was but yesterday. The walls are

still in death agonies; the stones fall, the breaches cry out; the holes are wounds; the

trees bend and shudder, as if making an effort to escape.

This court, in 1815, was in better condition than i: is today. Structures

which have since

been pulled down formed redans. angles, and squares.

The English were barricaded there; the French effected an entrance. but could not maintain

their position. At the side of the chapel, one wing of the chateau. the only remnant which

estate of the manor of I lotsgomont, stands crumbling, one might almost say disembowelled.

The chateau served as donjon; the chapel served as block-house. There was work of extermi-

nation. The French, shot down from all sides, from behind the walls, from the roofs of the

barns, from the bottom of the cellars, through every window, through every air-hole, through

every chink in the stones, brought fagots and fired the walls and the men: the storm of

balls was answered by a tempest of flame.

A glimpse may be had in the ruined wing, through the iron-barred windows,

of the dismantled

chambers of a main building; the English guards lay in ambush in these chambers; the spiral

staircase, broken from foundation to roof, appears like the interior of a broken shell. The

staircase has two landings; the English, besieged in the staircase, and crowded upon The up-

per steps, had cut away the lower ones. These are large slabs of blue stone, now heaped to-

gether among the nettles. A dozen steps still cling to the wall: on the first is cut the

image of a trident. These inaccessible steps are firm in their sockets;

all the rest re-

sembles a toothless jawbone. Two old trees are there; one is dead, the other is wounded at

the root, and does not leaf out until April. Since 1850 it has begun to grow across the

staircase.

There was a massacre in the chapel. The interior, again restored to quiet, is strange. No

mass has been said there since the carnage. The altar remains, however--a clumsy wooden al-

tar, backed by a wall of rough stone. Four whitewashed walls, a door opposite the altar,

two little arched windows, over the door a large wooden cmcifix, above the crucifix a square

opening in which is stuffed a bundle of straw; in a corner on the ground, an old glazed sash

all broken, such is this chapel. Near the altar hangs a wooden statue of St. Anne of the fif-

teenth century; the head of the infant Jesus has been carried away by a musket-shot. The

French, masters for a moment of the chapel, then dislodged, fired it. The flames filled this

ruin; it was a furnace; the door was burned, the floor was burned, but the wooden Christ

was not burned. The fire ate its way to his feet, the blackened stumps of which only are

visible; then it stopped. A miracle, say the country people. The infant Jesus, decapitated,

was not so fortunate as the Christ.

The walls are covered with inscriptions. Near the feet of the Christ we read this

name: Henquincz. Then these others: Conde de Rio Major Marques y Marquess de

Amagn (Habana). There are French names with exclamation points, signs of anger.

The wall was whitewashed in 1819. The nations were insulting each other

un it.

At the door of this chapel a body was picked up holding an axe in its hand. This

body was that of second-lieutenant Legros.

On coming out of the chapel, a well is seen at the left. There are two in this

yard. You ask: why is there no bucket and no pulley to this one.? Because no

water is drawn from it now. Why is no more water drawn from it? Because it is full

of skeletons.

The last man who drew water from that well was Guillaume Van Kylsom. He was a

peasant, who lived in Hougomont, and was gardener there. On the 18th of June,

1815, his family fled and hid in the woods.

The forest about the Abbey of Villiers concealed for several days and several

nights all that scattered and distressed population. Even now certain vestiges

may be distinguished, such as old trunks of scorched trees, which mark

the place

of these poor trembling bivouacs in the depths of the thickets.

Fuillaume Van Kylsom remained at Hougomont, "to take care of the chateau,"

and

hid in the cellar. The English discovered him there. He was torn from his hiding

place, and, with blows of the flat of their swords, the soldiers compelled this

frightened man to wait upon them. They were thirsty; this Guillaume brought

them

drink. It was from this well that he drew the water. Many drank their last

quaff.

This well, where drank so many of the dead, must die itself also.

After the action, there was haste to bury the corpses. Death has its own

way of

embittering victory, and it causes glory to be followed by pestilence.

Typhus is

the successor ol triumph. This well was deep, it was made a sepulchre.

Three

hundred desd were thrown into it. Perhaps with too much haste. Were they

all

dead? Tradition says no. It appears that on the night after the burial,

feeble

voices were heard calling out from the well.

This well is isolated in the middle of the courtyard. Three walls, half

brick and

half stone, folded back like the leaves of a screen, and imitating a square

turret, surround it on three sides. The fourth side is open. On that side the wa-

ter is drawn. The back wall has a sort of shapeless bull's-eye, perhaps

a hole

made by a shell. This turret had a roof. of which only the beams remain. The iron

that sustains the wall on the right is in the shape of a cross. You bend over

the well, the eye is lost in a deep brick cylinder, which is filled with an accum-

ulation of shadows. All around it, the bottom of the walls is covered by

nettles.

This well has not in front the large blue flagging stone which serves as a curb

for all the wells of Belgium. The blue stone is re-placed by a cross-bar

on

which rest five or six misshapen wooden stumps, knotty and hardened, that

resem-

ble huge bones. There is no longer either bucket, or chain, or pulley;

but the stone

basin is still there which served for the waste water. The rain water gathers there,

and fron time to time a bird from the neighbouring forest comes to drink and flies

away.

One house among these ruins, the farm-home. is still inhabited. The door

of this

house opens upon the court-yard. By the side of pretty Gothic key-hole

plate

there is upon the door a handful of iron in trefoil, slanting forward.

At the

moment that the Hanover ian lieutenant Wilda was seizing this to take refuge in

the farm house, a French sapper struck off his hand with the blow of an axe.

The family which occupies the house calls the former gardener, Van Kylsom,

long

since dead, its grandfather. A grey-haired woman said to us: "I was there. I

was three years old. My sister, larger, was afraid, and cried. They carried

us

away into the woods; I was in my mother's arms. They laid their ears to

the

ground to listen. For my part, I mimicked the cannon, and I went boom,

boom."

One of the yard doors, on the left, we have said, opens into the orchard.

The orchard is terrible.

It is in the three parts, one might almost say in three acts. The first part

is a garden, the second is the orchard, the third is a wood. These three parts

have a common indosure; on the sick of the entrance the buildings of the chateau

and the farm, on the left a hedge, on the right a wall, at the back a wall. The

wall on theright is of brick, the wall on the back is of stone. The garden is

entered first. It is sloping, planted with currant bushes, covered with wild

vegetation, and terminated by a terrace of cut stone, with balusters with a

double swell. It is a seignorial garden, in this first French style, which pre-

ceded the modern; now ruins and .briers. The pilasters are surmounted by globes

which look like stone cannon-balls. We count forty-three balusters still in their

places; the others are lying in the grass, nearly all show some scratches of

musketry. A broken baluster remains upright like a broken leg.

It is in this garden, which is lower than the orchard, that six of the first

Light Voltigeurs, having penetrated thither, and being unable to escape,

caught

and trapped like bears in a pit, engaged in a battle with two Hanoverian compan-

ies, one of which was armed with carbines. The Hanoverians were ranged

along

these balusters, and fired from above. These voltigeurs, answering from

below,

six against two hundred, intrepid, with the currant bushes only for a shelter,

took a quarter of an hour to die.

You rise a few steps, and from the garden pass into the orchard proper. There,

in these few square yards, fifteen hundred men fell in less than a hour.

The wall

seems ready to recommence the combat. The thirty-eight loopholes, pierced

by

the English at irregular heights, are there yet. In front of the sixteenth, lie two

English tombs of granite. There are no loopholes except in the south-wall, the

principal attack came from that side. This wall is concealed on the outside by

a large quickset hedge; the French came up, thinking there was nothing in their

way but the hedge, crossed it, and found the wall, an obstacle and an ambush,

the English Guards behind, the thirty-eight loopholes pouring forth their fire

at once, a storm of grape and of balls; and Soye's brigade broke there. Waterloo

commenced thus.

The orchard, however, was taken. They had no scaling ladders, but the French

climbed the wall with their hands. They fought hand to hand under the trees.

All this grass was soaked with blood. A battalion from Nassau, seven hundred

men, was annihilated there. On the outside, the wall against which the two bat-

teries of Kellermann were directed, is gnawed by grape.

This orchard is as responsive as any other to the month of May. It has its

golden blossoms and its daisies; the grass is high; farm horses are grazing;

lines on which clothes are drying cross the intervals between the trees, making

travellers bend their heads; you walk over that sward, and your foot sinks in

the path of the mole. In the midst of the grass you notice an uprooted trunk,

lying on the ground, but still growing green. Major Blackmann leaned back against

it to die. Under a large tree near by fell the German general, Duplat, of a

French family which fled on the revocation of the edict of Nantes. Close beside

it leans a diseased old apple tree swathed in a bandage of straw and loam.

Nearly

all the apple trees are falling from old age. There is not one which does not

show its cannon ball or its musket shot. Skeletons of dead trees abound in this

orchard. Crows fly in the branches; beyond it is a wood full of violets.

Bauduin killed, Foy wounded, fire, slaughter, carnage, a brook made of English

blood, of German blood, and of French blood, mingled in fury; a well filled with

corpses, the regiment of Nassau and the regiment of Brunswick destroyed, Duplat

killed, Blackmann killed, the English Guards crippled, twenty French battalions,

out of the forty of Reille's corps, decimated, three thousand men, in this

one

ruin of Hougomont, sabred, slashed, slaughtered, shot, burned; and all this in

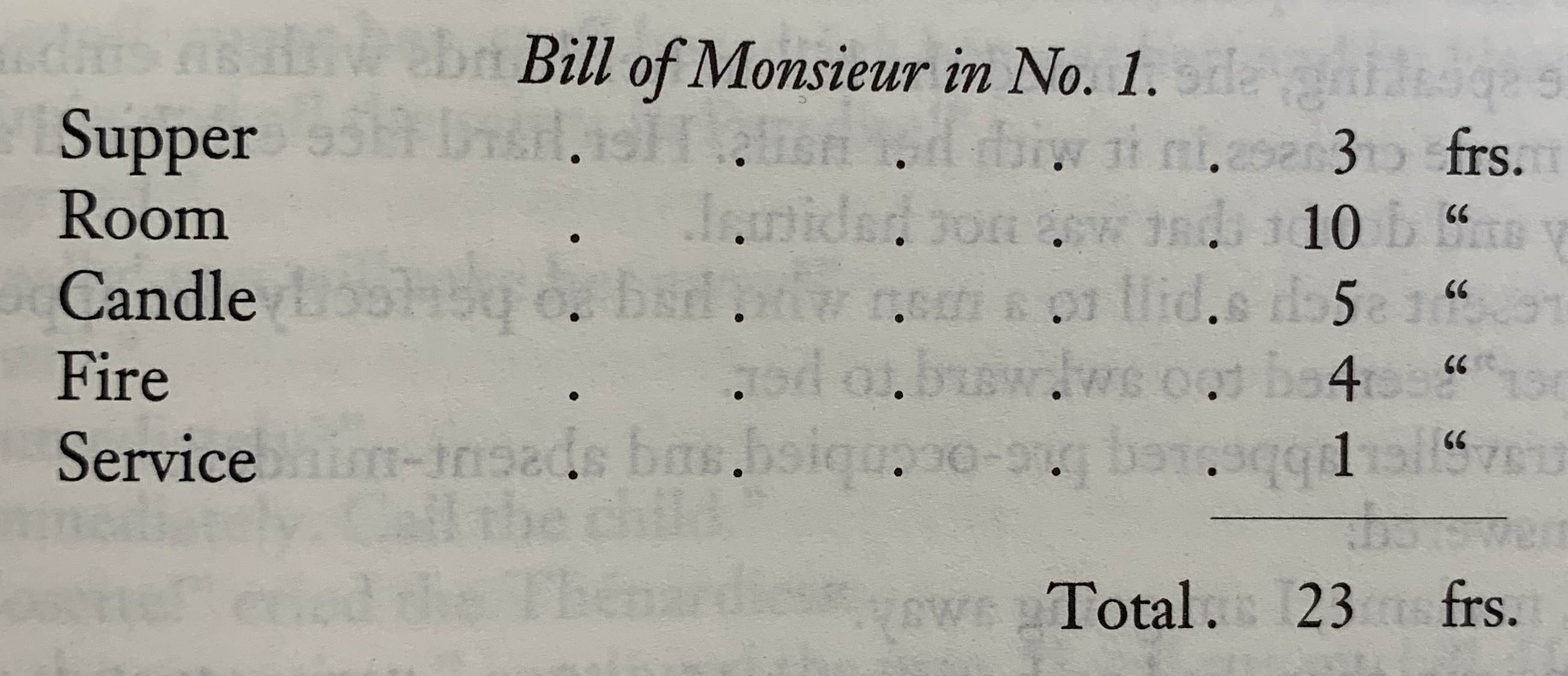

order that today a peasant may say to a traveller: Monsieur, give me three

francs; if you like, I will explain to you the affair of Waterloo.

III. THE 18TH OF JUNE, 1815

LET us go back, for such is the stow-teller's privilege, and place ourselves

in the year 1815, a little before the date of the commencement of the action

narrated in the first part of this book.

Had it not rained on the night of the 17th of June, 1815, the future of Europe

would have been changed. A few drops of water more or less prostrated Napoleon.

That Waterloo should be the end of Austerlitz, Providence needed only a little

rain, and an unseasonable cloud crossing thee sky sufficed for the overthrow of

a world:

The battle of Waterloo--and this gave Blucher time to come up--could not be com-

menced before half-past eleven. Why? Because the ground was soft. It was neces-

sary to wait for it to acquire some little firmness that the artillery

could manoeuvre.

Napoleon was an artillery officer, and he never forgot it. The foundation of

this prodigious captain was the man who, in his report to the Directory upon

Aboukir, said: Such of our balls killed six men. All his plans of battle were

made for projectiles. To converge. the artillery upon a given point was

his key

of victory. tk f 'cto He treated the strategy of the hostile general as a cit-

adel, and battered it to a breach. He overwhelmed the weak point with grape;

he joined and resolved battles with cannon. There was marksmanship in his gen-

ius. To destroy squares, to pulverise regiments, to break lines, to crush and

disperse masses, all this was for him, to strike, strike, strike incessantly,

and he entrusted this duty to the cannon ball. A formidable method, which,

joined to genius, made this sombre athlete of the pugilism of war invincible

for fifteen years.

On the 18th of June, 1815, he counted on his artillery the more because he had

the advantage in numbers. Wellington had only a hundred and fifty-nine guns;

Napoleon had two hundred and forty.

Had the ground been dry, and the artillery able to move, the ac-tion would have

been commenced at six o'clock in the morning. The battle would have been won

and finished at two o'clock, three hours before the Prussians turned the scale

of fortune.

How much fault is there on the part of Napoleon in the loss of this battle? Is

the shipwreck to be imputed to the pilot?

Was the evident physical decline of Napoleon accompanied at this time by a cor-

responding mental decline? had his twenty years of war worn out the sword as

well as the sheath, the soul as well as the body? was the veteran injuriously

felt in the captain? in a word, was that genius, as many considerable historians

have thought, under an eclipse? had he put on a frenzy to disguise his enfeeble-

ment from himself? did he begin to waver, and be bewildered by a random

blast?

was he becoming, a grave fault in a general, careless of danger? in that class

of material great men who may be called the giants of action, is there an age

when their genius becomes short-sighted? Old age has no hold on the geniuses of

the ideal; for the Dantes and the Michael Angelos, to grow old is to grow

great;

for the Hannibals and the Bonapartes is it to grow less? had Napoleon lost his

clear sense of victory? could he no longer recognise the shoal, no longer div-

ine the snare, no longer discern the crumbling edge of the abyss? had he

lost

the instinct of disaster? was he, who formerly knew all the paths of triumph,

and who, from the height of his flashing car, pointed them out with sovereign

finger, now under such dark hallucination as to drive his tumultuous train of

legions over the precipices? was he seized, at forty-six years, with a

sup-

reme madness? was this titanic driver of Destiny now only a monstrous break?

neck?

We think not.

His plan of battle was, all confess, a masterpiece. To march straight to

the

centre of the allied line, pierce the enemy, cut them in two, push the British

half upon Hal and the Prussian half upon Tongres, make of Wellington and Blucher

two fragments, carry Mont Saint Jean, seize Brussels, throw the German into the

Rhine, and the Englishman into the sea. All this, for Napoleon, was in this bat-

tle. What would follow, anybody can see.

We do not, of course, profess to give here the history of Waterloo; one of the

scenes that gave rise to the drama which we are describing hangs upon that battle;

but the history of the battle is not our subject; that history moreover is told,

and told in a masterly way, from one point of view by Napoleon, from the other

point of view by Charras. As for us, we leave the two historians to their

contest;

we are only a witness at a distance, a passer in the plain, a seeker bending over

this ground kneaded with human flesh, taking perhaps appearances for realities;

we have no right to cope in the name of science with a mass of facts in which

there is doubtless some mirage; we have neither the military experience nor the

strategic ability which authorises a system; in our opinion, a chain of accidents

overruled both captains at Waterloo; and when destiny is called in this mysterious

accused, we judge like the people, that artless judge.

IV A

THOSE who would get a clear idea of the battle of Waterloo have only to lay

down upon the ground in their mind a capital A. The left stroke of the t'-s

the road from Nivelles, the right stroke is the road from. Genappe, the cross

of the A is the sunken road from Ohain to Braine l'Alleud. The top of the A

is Mont Saint Jean, Wellington is there; the left-hand lower point is Hougomont

Reille is there with Jerome Bonaparte; the right-hand lower t:iutint is La Belle

Alliance, Napoleon is there. A little below the point where Zaciross of the A

meets and cuts the right stroke, is La Haie Sainte. At the ule of this cross is

the precise point where the final battle-word was hero. Spoken. There the lion

is placed, the involuntary symbol of the supreme heroism: of the Imperial

Guard.

The triangle contained at the top of the A, between the two strokes between the

two strokes and the cross. is the plateau Uf Mn: Saint ir.tn I he -mil:- gle

for this plateau was the whole of the battle.

The wings of the two tanks extended to the right and kit of the two roads from

Genappe and from Nivelks D'Erlon opposite Picton. Reille opposite Hill.

Behind the point of the A, behind the plateau of Mont SaintJean, is the forest

of Soignes.

As to the plain itself, we must imagine a vast undulating country each wave com-

manding the next, and these undulations rising towards Mont Saint Jean, are

there bounded by the forest.

Two hostile armies upon a field of battle are two wrestlers. Their arms are locked;

each seeks to throw the other. They grasp at every aid; a thicket is a point of

support; a corner of a wall is a brace for the shoulder; for lack of a few sheds

to lean upon a regiment loses its footing; a depression in the plain, movement of

the soil, a convenient cross path, a wood, a ravine, may catch the heel of this col-

ossus which is called an army, and prevent him from falling. He who leaves the field

is beaten. Hence, for the responsible chief, the necessity of examining the smallest

tuft of trees and appreciating the slightest details of contour.

Both generals had carefully studied the plain of Mont Saint Jean, now called the

plain of Waterloo. Already in the preceding year, Wellington, with the sagacity of

prescience, had examined it as a possible site for a great battle. On thisground

and for this contest Wellington had the favourable side, Napoleon the unfavourable.

The English army was above, the French army below.

To sketch here the appearance of Napoleon, on horseback, glass in hand, upon the

heights of Rossomtne, at dawn on the 18th of June, 1815, would be almost superfluous.

Before we point him out, everybody has seen him. This calm profile under the little

chapeau of the school of Brienne, this green uniform, the white facings concealing

the stars on his breast, the overcoat concealing the epaulets, the bit of red sash

under the waistcoat, the leather breeches, the white horse with his housings of pur-

ple velvet with crowned N.'s and eagles on the corners, the Hessian boots over silk

stockings, the silver spurs, the Marengo sword, this whole form of the last Caesar

lives in all imaginations, applauded by half the world, reprobated by the rest.

That form has long been fully illuminated; it did have a certain traditional obscur-

ity through which most heroes pass, and which always veils the truth for a longer

or shorter time; but now the history is luminous and complete.

This light of history is pitiless; it has this strange and divine quality that, all

luminous as it is, and precisely because it is luminous, it often casts a shadow

just where we saw a radiance; of the same man it makes two different phantoms, and

the one attacks and punishes the other, and the darkness of the despot struggles

with the splendour of the captain. Hence results a truer measure in the final judg-

ment of the nations. Babylon violated lessens Alexander; Rome enslaved lessens Cae-

sar; massacred Jerusalem lessens Titus. Tyranny lessens Titus. Tyranny

follows the

tyrant. It is woe to a man to leave behind him a shadow which has his form.

V. THE QUID OBSCURUM OF BATTLES

EVERBODY KNOWS the first phase of this battle; the difficult opening, uncertain,

hesitating, threatening for both armies, but for the English still more than for

the French.

It had rained all night; the ground was softened by the shower; water lay here

and there in the hollows of the plains as in basins; at some points the wheels

sank into the axles; the horses' girths dripped with liquid mud; had not the wheat

and rye spread down by that multitude of advancing carts filled the ruts and made

a bed under the wheels, all movement, particularly in the valleys on the side of

Papelotte, would have been impossible.

The affair opened late; Napoleon, as we have explained, had a habit of holding

all his artillery in hand like a pistol, aiming now at one point, anon at another

point of the battle, and he desired to wait until the field-batteries could wheel

and gallop freely; for this the sun must come out and dry the ground. But the sun

did not come out. He had not now the field of Austerlitz. When the first gun was

fired, the English General Colville looked at his watch and noted that it was

thirty-five minutes past eleven.

The battle commenced with fury, more fury perhaps than the emperor would have

wished, by the left wing of the French at Hougomont. At the same time Napoleon

attacked the centre by hurling the brigade of Quiot upon La Haie Sainte, and Ney

pushed the right wing of the French against the left wing of the English

which rested upon Papelotte.

The attack upon Hougomont was partly a feint; to draw Wellington that way, to make

him incline to the left; this was the plan. This plan would have succeeded had not

the four companies of the English Guards, and the brave Belgian; of Perponcher's

division, resolutely held the position, enabling Wellington, instead of massing

his forces upon that point, to limit himself to reinforcing them only by four add-

itional companies of guards, and a Brunswick battalion.

The attack of the French right wing upon Papelotte was intended to overwhelm the

English left, cut the Brussels road, bar passage of the Prussians, should

they come,

to carry Mont Saint Jean drive back Wellinton upon Hougomont, from thence upon Braine

l'Alleud, from thence upon Hal; nothing is clearer. With the exception of a few inci-

dents, this attack succeeded. Papelotte was taken; La Haie Sainte was carried.

Note a circumstance. There were in the English infantry, particularly in Kempt's bri-

gade, many new recruits. These young soldiers, before our formidable infantry, were

heroic; their inexperience bore itself boldly in the affair; they did especially good

service as skirmishers; the soldier as a skirmisher, to some extent left to himself,

becomes, so to speak, his own general; these recruits exhibited something of French

invention invention and French fury. This raw infantry showed enthusiasm. That dis-

pleased Wellington.

After the capture of La Haie Sainte, the battle wavered.

There is in this day from noon to four o'clock, an obscure interval; the middle of

this battle is almost indistinct, and partakes of the thickness of the conflict.

Twilight was gathering. You could perceive vast fluctuations in this mist, a giddy

mirage, implements of war now almost unknown, the flaming colbacks, the waving sabre-

taches, the crossed shoulder-belts, the grenade cartridge boxes, the dolmans of the

hussars, the red boots with a thousand creases, the heavy shakos festooned with

fringe, the almost black infantry of Brunswick united with the scarlet infantry of

England, the English soldiers with great white circular pads on their sleeves

for

epaulets, the Hanoverian light horse, with their oblong leather cap with copper

bands and flowing plumes of red horse-hair, the Scotch with bare knees and plaids,

the large white gaiters of our grenadiers; tableaux, not strategic lines, the need

of Salvator Rosa, not of Gribeauval.

A certain amount of tempest always mingles with a battle, Quid obscurum, quid

divinum. Each historian traces the particular lineament which pleases him in this

hurly-burly. Whatever may be the combinations of the generals, the shock of armed

masses has incalculable recoils in action, the two plans of the two leaders enter

into each other, and are disarranged by each other. Such a point of the battle-

field swallows up more combatants than such another, as the more or less spongy

soil drinks up water thrown upon it faster or slower. You are obliged to pour out

more soldiers there than you thought. An unforeseen expenditure. The line of battle

waves and twists like a thread; streams of blood flow regardless of logic; the

fronts of the armies undulate; regiments entering or retiring make capes and gulfs;

all these shoals are continually swaying back and forth before each other; where

infantry was, artillery comes; where artillery was, cavalry rushes up, battalions

are smoke. There was something there; look for it; it is gone; the vistas are dis-

placed; the sombre folds advance and recoil; a kind of sepulchral wind pushes for-

wards, crowds back, swells and disperses these tragic multitudes. What

is a hand

to hand fight? an oscillation. A rigid mathematical plan tells the story of a min-

ute, and not a day. To paint a battle needs those mighty painters who have chaos

in their touch. Rembrandt is better than Vandermeulen. Vandemeulen, exact

at noon,

lies at three o'clock. Geometry deceives; the hurricane alone is true. This is

what gives Folard the right to contradict Polybius. We must add that there is always

a certain moment when the battle degenerates into a combat, particularises itself,

scatters into innumerable details, which, to borrow the expression of Napoleon him-

self. "belong rather to the biography of the regiments than to the history of the

army." The historian, in this case, evidently has the right of abridgment. He can

only seize upon the principal outlines of the struggle, and it is given to no nar-

rator, however conscientious he may be, to fix absolutely the form of this

hor-

rible cloud which is called a battle.

This, which is true of all great armed encounters, is particularly applicable to

Waterloo.

However, in the afternoon, at a certain moment, the battle assumed precision.

VI. FOUR O'CLOCK IN THE AFTERNOON

TOWARDS four o'clock the situation of the English army was serious. The Prince of

Orange commanded the centre, I ItII the right wing, Pieton the left wing. The

Prince of Orange. desperate and intrepid, cried to the!Janosto-Belgian%:

Nassau!

Brunswick never retreat! Hill, exhausted, had fallen back upon Wellington. Picion

was dead. At the very moment that the English had taken from the French the colours

of the 105th of the line, the French had killed General Picton by a ball through

the head. For Wellington the battle had two points of support, I Iougonit

nit and

la!hale Sainte; Hougomont still held out, but was burning; La I laic Sainte had

been taken. Of the German battalion which defended it, forty-two men only survived;

all the officers, except five, were dead or prisoners. Three thousand combatants

were massacred in that grange. A sergeant of the English Guards, the best boxer

in England. reputed invulnerable by his comrades, had been killed by a

little

French drummer. Baring had been dislodged. Allen put to the sword. Several col-

ours had been lost, one belonging to Allen's division, and one to the Luneburg

battalion, borne by a prince of the family of DeuxPouts. The Scotch Grays were no

more: Ponsonby's heavy dragoons had been cut to pieces. That valiant cavalry had

given way before the lancers of Bro and the cuirassiers of Travers; of

their

twelve hundred horses there remained six hundred; of three lieutnant-colonels,

two lay on the ground, Hamilton wounded, Mather killed. Ponsonby had tallest.

pierced with seven thructc of a lance. Gordon was dead, Marsh was dead. Two slivi,

innc, the fifth aral the sixth. were destroyed.

Hougomont yielding. La Haie Sainte takcti, there was but one knot left, the

centre. That still held. Wellington reinforced it called thither Hill who was

at Merbe Braine, and Chasse who was at Braine l'Alleud

The centre of the English army, slightly concave, very dense and very compact,

held a strong position. It occupied the plateau of Mont Saint Jean, with the vil-

lage behind it and in front the declivity, which at that time was steep. At the

rear it rested on this strong stone-house, then an outlying property of Nivelles,

which marks the intersection of the roads, a sixteenth century pile so solid that

the balls ricocheted against it without injuring it. All about the plateau,

the English

had cut away the hedges here and there, made embrasures in the hawthorns,

thrust the mouth of a cannon between two branches, made loopholes in the thickets.

Their artillery was in ambush under the shrubbery. This punic labour, undoubtedly

fair in war, which allows snares, was so well done that Haxo, sent by the emperor

at nine o'clock in the morning to reconnoitre the enemy's batteries, saw nothing

of it, and returned to tell Napoleon that there was no obstacle, except the two

barricades across the Nivelles and Genappe roads. It was the season when grain is

at its height; upon the verge of the plateau, a battalion of Keropes brigade, the

95th, armed with carbines, was lying in the tall wheat.

Thus supported and protected, the centre of the Anglo-Dutch army was well situated.

The danger of this position was the forest of Soignes, then contiguous

to the bat-

tle-field and separated by the ponds of Groenendael and Boitsfort. An army could not

retreat there without being routed; regiments would have been dissolved immediately,

and the artillery would have been lost in the swamps. A retreat, according to the

opinion of many military men--contested by others, it is true--would have been an

utter rout.

'Wellington reinforced this centre by one of Chasse's brigades, taken from the right

wing, and one of Wincke's from the left in addition to Clinton's division. To his

English, to Halkett's regiments, to Mitchell's brigade, to Maitland's guards,

he

gave as supports the infantry of Brunswick, the Nassau contingent, Kleimansegge's

Hanovenans, and Ompteda's Germans. The right wing, as Charras says, was bent back

behind the centre. An enormous battery was faced with sand-bags at the place where

now stands what is called "the Waterloo Museum." Wellington had besides, in a lit-

tle depression of the ground, Somerset's Horse Guards, fourteen hundred. This was

the other half of that English cavalry, so justly celebrated. Ponsonby destroyed,

Somerset was left.

The battery, which, finished, would have been almost a redoubt, was disposed behind

a very low garden wall, hastily covered with sand-bags and a broad, sloping bank of

earth. This work was not finished; they bad not time to stockade it.

Wellington, anxious, but impassible, was on horseback, and remained there the whole

day in the same attitude, a little in from of the old mill of Mont Saint Jean, which

is still standing. under an elm which an Englishman, an enthusiastic vandal, has

since bought for two hundred francs, cut down and carried away. Wellington

was

frigidly heroic. The balls rained down. His aide-de-camp, Gordon, had just

fallen

at his side. Lord Hill, showing him a bursting shell, said: My Lord, what are your

instructions. and what orders do you leave us, if you allow yourself to

be killed?--

To follow my example, answered Wellington. To Clinton, he said laconically: Hold this

spot to the last man. The day was clearly going badly. Wellington cried to his old

companions of Talavera, Vittoria, and Salamanca: Boys! We must not be beat: what

would they say of us in England!

About four o'clock, the English line staggered backwards. All at once only the art-

illery and the sharp-shooters were seen on the crest of the plateau, the

rest disap-

peared; the regiments, driven by the shells and bullets of the French, fell back

into the valley now crossed by the cow-path of the farm of Mont Saint Jean;

a retro-

grade moyement took place, the battle front of the English way slipping.

away, Well-

ington gave ground. Beginning retreat! cried Napoleon.

VII. NAPOLEON IN GOOD HUMOR

THE emperor, although sick and hurt in his saddle by a local affliction,

had never

been in so good humour as on that day, Since morning, his impenetrable countenance

had worn a smile. On the 18th of June. 1815, that profound soul masked

in marble, shone

obscurely forth. The dark-browned man of Austerlitz was gay at Waterloo.

The greatest,

when foredoomed, present these contradictions. Our joys are shaded. The

perfect smile

belongs to God alone.

Ridet Caesar, Pompeiuts flebit, said the legionaries of the Fulminatrix Legion. Pom-

pey at this time was not to weep. but it is certain that Caesar laughed.

From the previous evening, and in the night, at one o'cle,eh. exploring on horseback,

in the tempest and the rain, with Itertrant the hills near Rossomtne, and gratified

to see the long line of the English fires illuminating all the horizon from Frischemont

to Braine-l'Alleud, it had seemed to him that destiny, for which he had

made an

appointment. for a certain day upon the field of Watertrloo, was punctual: he stopped

his horse. and remained some time motionless, watching the lightning and listening

to the thunder; this fatalist was heard to utter in the darkness these myserious

words: "We are in accord." Napoleon was deceived. They were no longer in accord.

He had not taken a moment's sleep; every instant of that night had brought him a new

joy. He passed along the whole line of the advanced guards, stopping here and

there

to speak to the pickets. At half-past two, near the wood of Hougomont, he heard the

tread of a column in march; he thought for a moment that Wellington was falling back.

He said: It is the English rear guard startineo get away. I shall take the six thou-

sand Englishmen who have just arrived at Ostend prisoners. He chatted freely; he had

recovered that animation of the disembarkation of the first of March; when he showed

to the Grand Marshal the enthusiastic peasant of Gulf Juan crying: Well, Bertrand,

there is a reinforcement already! On the night of the 17th of June, he made fun of

Wellington: This little Englishman must have his lesson, said Napoleon. The rain re-

doubled; it thundered while the emperor was speaking.

At half-past three in the morning one illusion was gone; officers sent out on a recon-

naissance announced to him that the enemy was making no movement. Nothing was stir-

ring, not a bivouac fire was extinguished. The English army was asleep. Deep silence

was upon the earth; there was no noise save in the sky. At four o'clock, a peasant

was brought to him by the scouts; this peasant had acted as guide to a brigade of

English cavalry, probably Vivian's brigade on its way to take position at the vil-

lage of Ohain, at the extreme left. At five o'clock, two Belgian deserters reported

to him that they had just left their regiment, and that the English army was expect-

ing a battle. So much the better! exclaimed Napoleon, I would much rather cut them

to pieces than repulse them.

In the morning, he alighted in the mud, upon the high bank at the corner of the road

from Planchenoit, had a kitchen table and a peasant's chair brought from the farm of

Rossomme, sat down, with a bunch of straw for a carpet, and spread out upon the table

the plan of the battle-field, saying to Soult: "Pretty chequer-board!"

In consequence of the night's rain, the convoys of provisions, mired in the softened

roads, had not arrived at dawn; the soldiers had not slept, and were wet and fasting;

but for all this Napoleon cried out joyfully to Ney: We have ninety chances

in a hundred.

At eight o'clock the emperor's breakfast was brought. He had invited several generals.

While breakfasting, it was related, that on the night but one before, Wellington was at

a ball in Brussels, given by the Duchess of Somerset; and Soult, rude soldier that he

was, with his archbishop's face, said: The ball is today. The emperor jested with Ney,

who said: Wellington will not be so simple as to wait for your majesty. This was his

manner usually. He was fond of joking, says Fleury de Chaboulon. His character

at bottom

was a playful humour, says Gourgaud. He abounded in pleasantries, oftener

grotesque

than witty, says Benjamin Constant. These gaieties of a giant are worthy

of remembrance.

He called his grenadier, "tbr growlers;" he would pinch their ears and would pull their

mustaches. The emperor did nothing but play tricks on us: so one of them said. During

the mysterious voyage from the Wand of Etta to France, on the 27th of February, in the

open sea. the French brig-of-war Zephyr having met the brig Inconstant, on which Napol-

eon was concealed, and having asked the Inconstant for news of Napoleon,

the emperor,

who still had on his hat the white and amaranth cockade, sprinkled with bees, adopted

by him in the island of Elba, took the speaking trumpet, with a laugh,

and answered

himself: the emperor is getting on finely. He who laughs in this way is on familiar

terms with events; Napoleon had several of these bursts of laughter during his Water-

loo breakfast. After breakfast. for a quarter of an hour, he collected his thoughts:

then two generals were seated on the bundle of straw, pen in hand, and

paper on knee,

and the emperor dictated the order of battle.

At nine o'clock, at the instant when the French army. drawn up and set in motion in five

columns, was deployed, the divisions urn two lines. the artillery between the brigades.

music at the head. playing marches, with the rolling of drums and the sounding

of trum-

pets--mighty, vast, joyous,---a sea of casques. sabres, and bayonets in

the horizon, the

emperor. excited, cried out, and repeated: "Magnificent! magnificent!"

Between nine o'clock and half-past ten, the whole army, which seems incredible, had tak-

en position, and Iva, ranged in six lines, forming, to repeat the expression of the em-

peror, "the figure of six V's." A few moments after the formation

of the line of battle,

in the midst of this profound silence, like that at the commencement of

a storm, which

precedes the fight, seeing as they filed by the three batteries of twelve

pounders, de-

tached by his orders from the three corps of D'Esion, Relic, and Lobau, to commence the

action In attacking Mont Saint Jean at the intersection of the roads from NI: elks and

Genappe, the emperor struck I inso on the shoulder, There are twenty- four pretty girls,

General.

Sure of the event, he encouraged with a smile, as they passed before him,

the

company of sappers of the first corps, which he had designated to erect

barr-

icades in Mont Saint Jean. as soon as the village was carried. All this serenity

was disturbed by but a word of haughty pity; on seeing, massed at his left,

at

a place where there is today a great tomb, those wonderful Scotch Grays,

with

their superb horses, he said: "It is a pity."

Then he mounted his horse, rode forward from Rossome, and chose for his point of

view a narrow grassy ridge, at the right ofthe road from Grenappe to Brussels,

which was his second station during the battle. The third station, that of seven

o'clock betweenLa Belle Alliance and La Wale Sainte is terrible; it is a consid-

erable hill which can still be seen, and behind which the guard was massed in a

depression of the plain. About this hill the balls ricocheted over the paved road

up to Napoleon. As at Brienne, he had over his headthe whistling of balls and bul-

lets. There have been gathered, old upon the spot pressed by his horse's feet,

crushed bullets, old sabreblades, and shapeless projectiles, eaten with

rust. Scara

rubigine. Some years ago, a sixty-pound shell was dug up there, still loaded, the

fuse having broken off even with the bomb. It was at this last station that the

emperor said to his guide Lacoste, a hostile peasant, frightened, tied to a hussar's

saddle, turning around at every volley of grape, and trying to hide behind Napoleon:

Dolt, this is shameful. You will get yourself shot in the back. He who writes these

lines has himself found in the loose slope of that hill, by turning up

the earth,

the remains of a bomb, disintegrated by the rust of forty-six years, and some old

bits of iron which broke like alder twigs in his finger.

The undulations of the diversely inclined plains, which were the theatre of the en-

counter of Napoleon and Wellington, are, as everybody knows, no longer what they

were on the 18th of June, 1815. In taking from that fatal field wherewith to make

its monument, its real form was destroyed: history, disconcerted, no longer recognises

herself upon it. To glorify it, it has been disfigured. Wellington, two years after-

wards, on seeing Waterloo, exclaimed: They have changed my battle-field Where to-

day is the great pyramid of earth surmounted by the lion, there was a ridge

which

sank away towards the Nivelles road in a practicable slope, but which, above the

Genappe road, was almost an escarpment. The elevation of this escarpment, silent

may be measured today by the height of the two great burial mounds which

embank

the road from Genappe to Brussels; the English tomb at the left, the German tomb

at the right. There is no French tomb. For France that whole plain is a sepulchre.

Thanks to thousands and thousands of loads of earth used in the mound of a hundred

and fifty feet high and a half a mile in circuit, the plateau of Mont St. Jean is

accessible by a gentle slope; on the day of the battle, especially on the side of

La Hale Sainte, the declivity was steep and abrupt. The descent was there so prec-

ipitous that the English artillery did not see the farm below them at the bottom

of the valley, the centre of the combat. On the 18th of June, 1815, the rain had

gullied out this steep descent still more; the mud made the ascent still more dif-

ficult; it was not merely laborious, but men actually stuck in the mire. Along the

crest of the plateau ran a sort of ditch, which could not possibly have been sus-

pected by a distant observer.

What was this ditch? we will tell. Braine l'Alleud is a village of Belgium. Ohain

is another. These villages, both hidden by the curving of the ground, are

con-

nected by a road about four miles long which crosses an undulating plain, often

burying itself in the hills like a furrow, so that at certain points it is a rav-

ine. In 1815, as now, this road cut the crest of the plateau of Mont Saint

Jean

between the two roads from Genappe and Nivelles; only, today it is on a level

with the plain; whereas then it was sunk between high bank,. It's two slopes were

taken away for the monumental mound. That road was and is still a trench for the

greater part of its length: a trench in some parts a dozen feet deep, the slopes

of which are so steep as to slide down here and there, especially in winter,

after showers. Accidents happen there. The road was so narrow at the entrance of

Braine l'Allend that a traveller was once crushed by a waggon as is attested by

a stone cross standing near the cemetery, which gives the name of the dead.

Mon-

sieur Bernard Petty, snerchant of Brussels, and the date of the accident, February,

1637,' It was so deep at the plateau of Mont Saint Jean, that a peasant, Matthew

Nicaise, had been crushed there in 1783 by thy falling of the bank, as another

stone cross attested; the top of this has disappeared in the changes, but its o-

verturned pedestal is still visible upon the sloping bank at the left of the road

between Li I laic Sainte and the farm of Mont Saint Jean.

On the day of the battle, this sunken road, of which nothing gave warning, along

the crest of Mont Saint Jean, a ditch at the summit of the escarpment, a trench

concealed by the ground, was invisible, that is to say terrible.

VIII. THE EMPEROR PUTS A QUESTION TO THE GUIDE LACOSTE

On the morning of Waterloo then, Napoleon was satisfied.

He was right; the plan of battle which he had conceived, as we have shown, was indeed

admirable.

After the battle was once commenced, its very diverse fortune, the resistance

of Hou-

gomont, the tenacity of I.a link Sainte, Banduin killed, For put hors de

ronthat, the unex-

pected wall against which Snye's brigade was broken, the fatal blunder of Gunk:it:not in

having neither grenades nor powder, the miring of the batteries, the fifteen pieces without

escort cut off by Uxbridge in a deep cut of a road, the slight effect of

the bombs that

fell within the English lines, burying themselves in the soil softened

by the rain and

only succeeding in making volcanoes of mud, so that the explosion was changed into a

splash, the uselessness of Pire's demonstration upon Braine I'Alleud, all

this cavalry,

fifteen squadrons, almost destroyed, the English right wing hardly disturbed, the left

wing hardly moved, the strange mistake of Ney in massing, instead of drawing

out, the

four divisions of the first corps, the depth of twenty-seven ranks and the front of two

hundred men offered up in this manner to grape, the frightful gaps made

by the balls

in these masses, the lack of connection between the attacking columns, the slanting bat-

tery suddenly unmasked upon their flank, Bourgeois, Donzelot, and Durutte entangled,

Quiot repulsed, Lieutenant Vieux, that Hercules sprung from the Polytechnic School,

wounded at the moment when he was beating down with the blows of an axe the door of La

Haic Sainte under the plunging fire of the English barricade barring the turn of the

road from Genappe to Brussels, Marcognet's caught between infantry and cavalry, shot

down at arm's length in the wheat field by Best and Pack, sabred by Ponsonby, his bat-

tery of seven pieces spiked, the Prince of Saxe Weimar holding and keeping Frischemont

and Smohain in spite of Count D'Erlon, the colours of the 105th taken, the colours of

the 43rd taken, this Prussian Black Hussar, brought in by the scouts of the flying col-

umn of three hundred chasseurs scouring the country between Wavre and Planchenoit,

the disquieting things that this prisoner had said, Grouchy's delay, the

fifteen hundred

men killed in less than an hour in the orchard of Hougomont, the eighteen hundred men

fallen its still less time around La Hale Sainte--all these stormy events, passing like

battle clouds before Napoleon, had hardly disturbed his countenance, and had not dark-

ened its imperial expression of certainty. Napoleon was accustomed to look

upon war

fixedly; he never made figure by figure the tedious addition of details; the figures

mattered little to him, provided they gave this total: Victory; though beginnings went

wrong he was not alarmed at it, he who believed himself master and possessor of the

end; he knew how to wait, believing himself beyond contingency, and he treated destiny

as an equal treats an equal. He appeared to say to Fate: thou would'st not dare.

Half light and half shadow, Napoleon felt himself protected in the right, and tolerated

in the wrong. He had, or believed that he had, a connivance, one might almost say com-

plicity, with events, equivalent to the ancient invulnerability. However, when one has

Beresina, Leipsic, and Fontainebleau behind him, it seems as if he might

distrust Wat-

erloo. A mysterious frown is becoming visible in the depths of the sky.

At the moment when Wellington drew back, Napoleon started up. He saw the

plateau of

Mont Saint Jean suddenly laid bare, and the front of the English army disappear.

It

rallied, but kept concealed. The emperor half rose in his stirrups. The flash of vic-

tory passed into his eyes.

Wellington hurled back on the forest of Soignes and destroyed; that was

the final over-

throw of England by France; it was Cressy Poitiers, Malplaquet, and Ramillies

aveng-

ed. The man of Marengo was wiping out Agincourt.

The emperor then, contemplating this terrible turn of fortune, swept his

glass for the

last time over every point of the battle-field. His guard standing behind

with grounded

arms, looked up to him with a sort of religion. He was reflecting; he was

examining

the slopes, noting the ascents, scrutinising the tuft of trees, the square

rye field, the

footpath; he seemed to count every bush. He looked for some time at the English barri-

cades on the two roads, two large abattis of trees, that on the Genappe

road above La

Haie Sainte, armed with two cannon, which alone, of all the English artillery,

bore

upon the bottom of the field of battle, and that of the Nivellei road where glistened

the Dutch bayonets of Chasse's brigade. He noticed near that barricade

the old chapel

of Saint Nicholas, painted white, which is at the corner of the cross-road

toward

Braine l'Alleud. He bent over and spoke in an under tone to the guide Lacoste. The guide

made a negative sign of the head, probably treacherous.

The emperor rose up and reflected. Wellington had fallen back. It remained only to com-

plete this repulse by a crushing charge.

Napoleon, turning abruptly, sent off a courier at full speed to Paris to announce that

the battle was won. Napoleon was one of those geniuses who rule the thunder. He had

found his thunderbolt. He ordered Milhaud's cuirassiers to carry the plateau of Mont

Saint Jean.

IX. THE UNLOOKED FOR

There were three thousand five hundred. They formed a line of half a mile. They

were gigantic men on colossal horses. There were twenty-six squadrons and

they

had behind them, as a suppot, the. division of Lefebvre Desnouettes, the

hundred

and six gendarmes d'elite, the Chasseurs of the Guard, seven hundred and

ninety-

seven men. and the Lancers of the Guard, eight hundred eighty lances They wore

casques with plumes, and cuirasses of wrought iron, with horse pistols in their

holsters and long sabre-swords. In the morning, they had been the admiration of

the whole army, when at nine o'clock, with trumpets sounding, and all the bands

playing, Veillons au salut de l'empire, they came, in heavy column, one of their bat-

teries on their flank, the other at their centre, and deployed in two ranks be-

tween the. Genappe road and Frischemont, and took their position of battle

in

this powerful second line, so wisely made up by Napoleon, which, having

at its ex-

treme left the cuirassiers of Kellerman, and at its extreme right the cuirassiers

of Milhaud, had, so to speak, two wings of iron.

Aide-de-camp Bernard brought them the emperor's order. Ney drew his sword and

placed himself at their head. The .enormous squadrons began to move.

Then was seen a fearful sight.

All this cavalry, with sabres drawn, banners waving and trumpets sounding, formed

in column by division, descended with an even movement and as one man--with the

precision of a bronze battering-ram opening a breach--the hill of La Belle Alli-

ance, sank into that formidable depth where so many men had already fallen, disa-

ppeared in the smoke, then, rising from this valley of shadow reappeared on the

other side, still compact and serried, mounting at full trot, through a cloud of

grape emptying itself upon them, the frightful acclivity of mud of the

plateau of

Mont Saint Jean. They rose, serious, menacing, imperturable; in the intervals of

the musketry and artillery could be heard the sound of this colossal tramp. Being

in two divisions, they formed two columns; Wathier's division had the right, De-

lord's the left. From a distance they would be taken for two immense serpents of

steel stretching themselves towards the crest of the plateau. That ran through

the battle like a prodigy.

Nothing like it had been seen since the taking of the grand redoubt at La Moscowa

by the heavy cavalry; Murat was not there, but Ney was there. It seemed as if this

mass had become a monster, and had but a single mind. Each squadron undulated

and swelled like the ring of a polyp. They could be seen through the thick

smoke, as

it was broken here and there. It was one pell-mell of casques, cries, sabres; a

furious bounding of horses among the cannon, and the flourish of trumpets, a ter-

rible and disciplined tumult; over all, the cuirasses, like the scales of a hydra.

These recitals appear to belong to another age. Something like this vision appeared,

doubtless, in the old Orphic epics which tell of centaurs, antique hippanthropes,

those titans with human faces, and chests like horses, whose gallop scaled Olympus,

horrible, invulnerable, sublime; at once gods and beasts.

An odd numerical coincidence, twenty-six battalions were to receive these twenty-

six squadrons. Behind the crest of the plateau. under cover of the masked battery,

the English infantry, formed in thirteen squares, two battalions to the square,

and upon two lines--seven on the first, and six oil the second--with musket to the

shoulder, and eye upon their sights, waiting calm, silent. and immovable. They

could not see the cuirassiers, and the cuirassiers could not see them.

They listened

to the rising of this tide of men They heard the increasing sound of three thousand

horses. the alternate and measured striking of their hoofs at full trot, the rattling

of the cuirasses, the clicking of the sabres, and a sort of fierce roar of the coming

host. There was a moment of fearful silence, then. suddenly, a long line of raised

arms brandishing sabres appeared above the crest, with casques, trumpets, and

standards, and three thousand faces with grey moustaches, crying. Vive l'emper-

eur! this cavalry debouched on the plateau, and it was like tin: beginning of an

earthquake.

All at once, tragic to relate, at the left of the English. and on our right, the

head of the column of cuirassiers reared with a frightful clamour. Arrived at the

culminating point of the crest, unmanageable, full of fury, and bent upon

the ex-

termination of the square, and cannons, the cuirassiers saw between themselves

and the English a ditch, a grave. It was the sunken road of Ohain.

It was a frightful moment. There was the ravine, unlooked for, yawning at the very

feet of the horses, two fathoms deep between its double slope. The second

rank

pushed in the first, the third pushed in the second; the horses reared,

threw them-

selves over, fell upon their backs, and struggled with their feet in the air, pil-

ing up and overturning their riders; no power to retreat: the whole column

was no-

thing but a projectile. The force acquired to crush the English crushed

the French.

The inexorable ravine could not yield until it was filled; riders and horses

roll-

ed in together pell-mell, grinding each other, making common flesh in this dreadful

gulf, and when this grave was full of living men, the rest marched over them and

passed on. Almost a third of Dubois' brigade sank into this abyss.

Here the loss of the battle began.

A local tradition. which evidently exaggerates, says that two thousand horses and

fifteen hundred men were hurled in the sunken road of Chain. This undoubtedly com-

prises all the other 'bodies thrown into this ravine on the morrow after the battle.

Napoleon, before ordering this charge of Milhaucrs cuirass.ier, had examined the

ground, but could not see tisk hollow road, which did not make even a wrinkle on the

surface of the plateau. Warurel. however, and put on his guard IT the little white

chapel which marks its junction with the Niceties road, he had, probably en the con-

tingency of an obstacle, put a quection to the guile Lan:str. The guide bad atom:

ern! no. It ma) al... be s:.61;ha: th, t.hal:c of a peasant's head came the entac-

trethe m Nap,Trnn.

Still other fatalities must arise.

Was it possible that Narleon riltoulil %, in Oa, battle: Wt no. Why? Because of

Wellington? Because of Blucher? No. Because of God.

For Bonaparte to be conqueror at Waterloo was not in the lay of the nineteenth cen-

tury. Another series of facts were preparing in which Napoleon had no place. The

ill-will of events had long been announced.

It was time that this vast man should fall.

The excessive weight of this man in human destiny disturbed the equilibrium. This

individual counted, of himself alone, more than the universe besides. These pleth-

oras of all human vitality concentrated in a single head, the world mounting to

the brain of one man, would be fatal to civilisation if they should endure. The

moment had come for incorruptible supreme equity to look to it. Probably

the prin-

ciples and elements upon which regular gravitations in the moral order as well as

in the material depend, began to murmur. Reeking blood, overcrowded cemeteries,

weeping mothers--these are formidable pleaders. When the earth is suffering

from a

surcharge, there are mysterious moanings from the deeps which the heavens hear.

Napoleon bad been impeached before the Infinite, and his fall was decreed.

He vexed God.

Waterloo is not a battle; it is the change of front of the universe.

X. THE PLATEAU OF MONT SAINT JEAN

AT the same time with the ravine, the artillery was unmasked.

Sixty cannon and the thirteen squares thundered and flashed into the cuirassiers.

The brave General Delord gave the military salute to the English battery. All the

English flying artillery took position in the squares at a gallop. The cuirassiers

had not even time to breathe. The disaster of the sunken road had decimated, but

not discouraged them. They were men who, diminished in number, grew greater in

heart.

Wathier's column alone had suffered from the disaster; Dc-lord's, which Ney bad

sent obliquely to the left, as if he had a presentiment of the snare, arrival en-

tire.

The cuirassiers hurled themselves upon the English squares.

At full gallop, with free rein, their sabres in their teeth, and their

pistols

in their hands, the attack began.

There are moments in battle when the soul hardens a man even to changing the

soldier into a statue, and all this; flesh becomes granite. The English

battalions,

desperately assailed, did not yield an inch.

Then it was frightful.

All sides of the English squares were attached at once, A whirlwind of

frenzy

enveloped them. This frigid infantry remained impassible. The first rank, with

knee on the ground, received the cuirassiers on their bayonets, the second

shot

them down; behind the second rank, the cannoneers loaded their guns, the

front

of the square opened, made way for an eruption of grape, and closed again.

The

cuirassiers answered by rushing upon them with crushing force,. Their great

horses

reared, trampled upon the ranks. leaped over the bayonets and fell, gigantic,

in the

midst of these four living walls. The balls made gaps in the ranks of the

cuirassiers,

the cuirassiers made breaches in the squares. Files of men disappeared,

ground

down beneath the horses' feet. Bayonets were buried in the bellies of these centaurs.

Hence a monstrosity of wounds never perhaps seen elsewhere. The squares. con-

sumed by this furious cavalry, closed up without wavering. Inexhaustible in grape,

they kept up an explosion in the midst of their assailant:. It was a monstrous sight.

These squares were battalions no longer, they were crates; these cuirassiers were

cavalry no longer, they were a tempest. Each square was a volcano attacked by a

thunder-cloud; the lava fought with the lightning.

The square on she extreme right, the most exposed of all, being in the

open field,

was almost annihilated at the first shock. It was formed of the 75th regiment of

highlanders. The piper in the centre, while the work of extermination wag going on,

profoundly oblivious of all about him, casting down his melancholy eye

full of the

shadows of forests and lakes, seated upon a drum, his bagpipe under his arm,

was playing his mountain airs. These Scotchmen died thinking of Ben Lothian, as

the Greeks died remembering Argos. The sabre of a cuirassier, striking

down the pi-

broch and the arm which bore it, caused the strain to cease by killing the player.

The cuirassiers, relatively few in number, lessened by the catastrophe

of the

ravine, had to contend with almost the whole the English army, but they

multiplied them-

selves, each man becoming equal to ten. Nevertheless some Hanoverian battalions

fell

back. Wellington saw it and remembered his cavalry. Had Napoleon, at that

very mo-

ment, remembered his infantry, he would have woin the battle. This forgetfulness was

his great fatal blunder.

Suddenly the assailiing cuirassers perceived that they were assailed, The English cavalry

was upon their back. Beroe them squares, behind them Somerset; Somerset, with the

fourteen hundred dragoon guards. Somerset had on his right Dornberg with his German

light-horse and on his left Trip, with the Belgian carbineers. The cuirassiers, attacked

front, flank, and rear, by infantry and cavalry,. were compelled to face in all directions.

What was that to them? They were a whirlwind. Their valour became unspeakable.

Besides, they had behind them the ever thundering artillery. All that was necessary in

order to wound such men in the back. One of their cuirasses, with a hole

in the left

shoulder-plate made by a musket ball, is in the collection of the Waterloo Museum.

With such Frenchmen only such Englishmen could cope.

It was no longer a conflict, it was a darkness, a fury, a giddy vortex

of souls and cou-

rage, a hurricane of sword-flashes. In an instant the fourteen hundred horse guards

were but eight hundred; their lieutenant, fell dead. Ney rushed up with the lancers and

chasseurs of Lefebvre-Desnouettes. The plateau of Mont Saint Jean was taken, retaken,

taken again. The cuirassiers left the ecavalry to return to the infantry, or more cor-

rectly, all this terrible multitude wrestled with each other without letting go their

hold. The squares still held. There were twelve assaults. Ney had four horses killed

under him. Half of the cuirassiers lay on the plateau. This struggle lasted two hours.

The English army was terribly shaken. There is no doubt, if they had not been crippled

in their first shock by the disaster of the sunken road, the cuirassiers would have

overwhelmed the centre, and decided the victory. This wonderful cavalry astounded Clin-

ton, who had seen Talavera and Badajos. Wellington, though three-fourths conquered,

was struck with heroic admiration. He said in a low voice: "splendid!"

The cuirassiers annihilated seven squares out of thirteen, took or spiked sixty pieces

of cannon, and took from the English regiments six colours, which three cuirassiers and

three chasseurs of the guard carried to the emperor before the farm of La Belle Alliance.

The situation of Wellington was growing worse. This strange battle was like a duel be-

tween two wounded infuriates who, while yet fighting and resisting, lose all their

blood. Which of the two shall fall first?

The struggle of the plateau continued.

How far did the cuirassiers penetrate? None can tell. One thing is certain:

the day

after the battle, a cuirassier and his horse were found dead under the frame of the hay-

scales at Mont Saint jean, at the point where the four roads from Nivelles, Genappe, La

Itulpe, and Brussels meet. This horseman had pierced the E.nglish lines. One of the men

who took away the body still lives at Mont Saint Jean. His name is Dehaze; he was then

eighteen years old.

Wellington felt that he was giving way. The crisis was upon him.

The cuirassiers had not succeeded, in this sense, that the centre was not. broken. All

holding the plateau, nobody held it, and in fact it remained for the most part with

the English. Wellington held the village and the crowning plain; Ney held only the crest

and the slope. On both sides they seemed rooted in this funebral soil.

But the enfeeblement of the English appeared irremediable. The haemorrhage

of this army was horrible. Kempt, on the left wing, called for reinforcements.

"Impossible," answered Wellington; "we must die on the spot we now occupy."

Almost at the same moment--singular coincidence which depicts the exhaustion

of both armies--Ney sent to Napoleon for infantry, and Napoleon exclaimed:

"Infantry! where does he expect me to take them! Does he expect me to make

them?"

However, the English army was farthest gone. The furious onslaughts of these

great squadrons with iron cuirasses and steel breastplates had ground up the

infantry. A few men about a flag marked the place of a regiment; battalions

were now commanded by captains or lieutenants. Alten's division, already so

cut up at La Haie Sainte, was almost destroyed; the intrepid Belgians of Van

Kluze's brigade strewed the rye field along the Nivelles road; there were

hardly any left of those Dutch grenadiers who, in 1811, joined to our ranks

in Spain, fought against Wellington, and who, Li 1815, rallied on the English

side, fought against Napoleon. The loss in officers was heavy. Lord Uxbridge,

who buried his leg next day, had a knee fractured. If, on the side of the

French, in this struggle of the cuirassiers, Delord, l'Heritier, Colbert, Dm:).

Travers, and Blancard were hors de combat, on the side of the English, Alten

was wounded, Barrie was wounded. Delancey was killed, Van Meeren was killed.

Ompteda was killed, the entire staff of Wellington was decimated, and England

had the worst share in this balance of blood. The second regiment of foot

guards had lost five lieutenant-colonels, four captains, and three ensigns;

the first battalion of the thirtieth infantry had lost twenty-four officers

and one hundred and twelve soldiers; the seventy-ninth Highlanders had twenty-

four officers wounded, eighteen officers killed, and four hundred and fifty

soldiers slain. Cumberland's Hanoverian hussars, an entire regiment, having

at its head Colonel Hacke, who was afterwards court-martialed and broken,

had drawn rein before the fight, and were in flight in the Forest of Soignes,

spreading the panic as far as Brussels. Carts, ammunition-wagons, baggage-

waggons, ambulances full of wounded, seeing the French gain ground, and ap-

proach the forest, lied precipitately; the Dutch, sabred by the French cav-

alry, cried murder! From Vert-Coucou to Groenendael, for a distance of near-

ly six miles in the direction towards Brussels, the roads, according to the