Introduction

Jorge Luis Borges arrived in Austin in September, tofii. The plane

that brought him flew for some hours on the edge of a terrible hurri-

cane, the same storm that destroyed several towns along the Texas

coast. The placid librarian and Uni-versity of Buenos Aires professor

could not fail to feel on that occasion--as he told us later--a mixture

of misgiving and excitement. Texas was for him an epic-laden dream.

When the dream came true that September day, it seemed the elements

had conspired to give him a heroic reception. Once the first Homeric

enthusiasms were over Borges settled down to the ordinary routine of a

visiting professor.

To Leopoldo Lugones

Leaving behind the babble of the plaza. I enter the Library. I feel,

almost physically, the gravitation of the books, the enveloping ser-

enity of order, time magically desiccated and preserved. Left and

right, absorbed in their shining dreams, the readers' momentary pro-

files are sketched by the light of their bright officious lamps, to

use Milton's hypallage. I remember having remembered that figure

before in this place, and afterwards that other epithet that also

defines these environs, the "arid camel" of the Lunario, and then

that hexameter from the Aeneid that uses the same artifice and sur-

passes artifice itself: lbant obscuri solo sub mete per umbras.

These reflections bring me to the door of your office. I go in; we

exchange a few words, conventional and cordial, and I give you this

book. If I am not mistaken• you were not disinclined to me. Lug-

ones, and you would have liked to like some piece of my work. That

never happened; but this time you turn the pages and read approv-

ingly a verse here and there--perhaps because you have recognized

your own voice in it, perhaps because deficient practice concerns

you less than solid theory.

At this point my dream dissolves, like water in water. The vast

library that surrounds me is on Mexico Street, not on Rodriguez

Pena, and you, Lugones, killed yourself early in '38. My vanity

and nostalgia have set up an impossible scene. Perhaps so (1 tell

mysel), but tomorrow I too will have died, and our times will

intermingle and chronology will be lost in a sphere of symbols.

And then in some way it will be right to claim that 1 have brought

you this book, and that you have accepted.

ed it.

J. L. B.

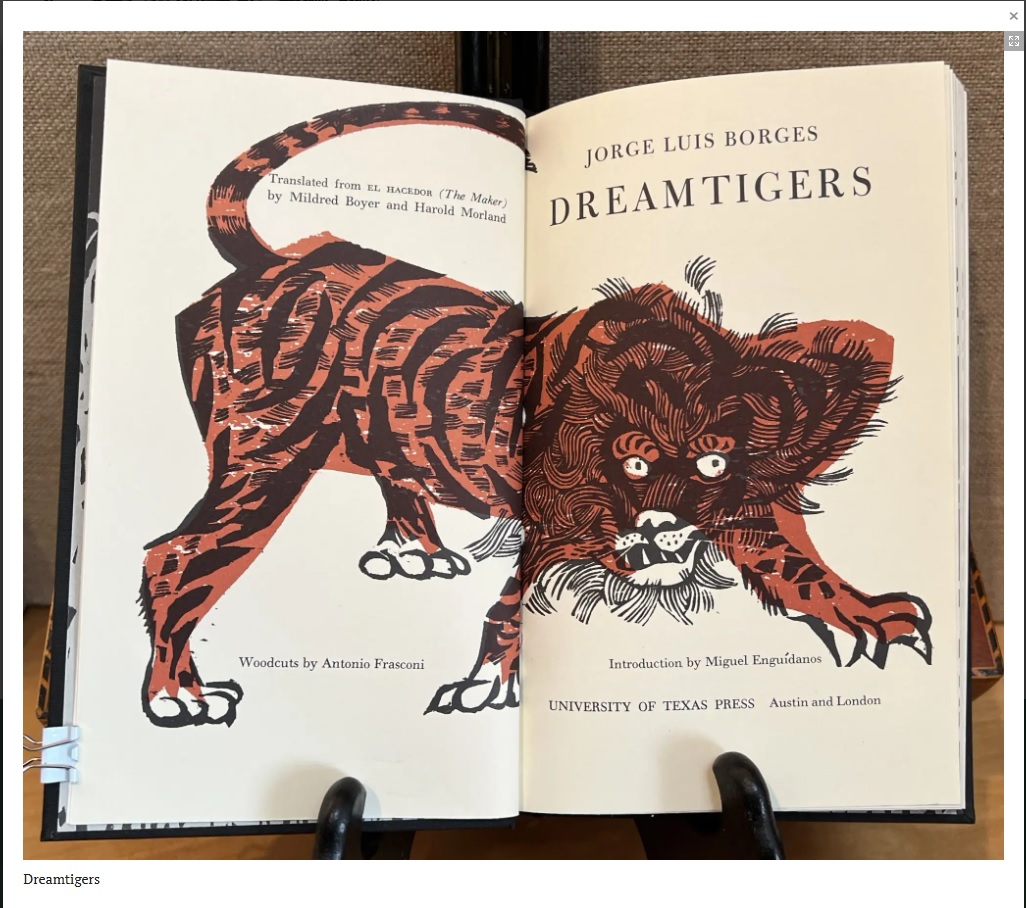

Dreamtigers

In my childhood I was a fervent worshiper of the tiger: not the

jaguar, the spotted "tiger" of the Amazonian tangles and the isles

of vegetation that float down the Parana', but that striped, Asia-

tic, royal tiger, that can be faced only by a man of war, on a

castle atop an elephant. I used to linger endlessly before one of

the cages at the zoo; I judged vast encyclopedias and books of

natural history by the splendor of their tigers. (I still rememb-

er those illustrations: I who cannot rightly recall the brow or

the smile of a woman ) Childhood passed away, and the tigers and

my passion for them grew old, but still they are in my dreams. At

that submerged or chaotic level they keep prevailing. And so, as

I sleep. some dream beguiles me, and suddenly I know I am dreaming.

Then I think: This is a dream, a pure diversion of my will; and

now that I have unlimited power. I am going to cause a tiger.

Oh, incompetence! Never can my dreams engender the wild beast

I long for. The tiger indeed appears, but stuffed or flimsy, or

with impure variations of shape, or of an implausible size, or

all too fleeting, or with a touch of the dog or the bird.

Toenails

Soft stockings coddle them by day and nail-bossed leather shoes

buttress them. but my toes refuse to pay attention. Nothing in-

terests them but emitting toenails. horny plates, semi-transpa-

rent and elastic, to defend themselves--from whom? Stupid and

mistrustful as they alone can be. they never for a moment stop

readying that tenuous armament. They reject the universe and its

ecstasy to keep forever elaborating useless sharp ends, which

rude Solingen scissors snip over and over again. Ninety days a-

long in the dawn of prenatal confinement, they established that

singular industry. When I am laid away, in an ash-colored house

provided with dead flowers and amulets, they will still go on

with their stubborn task. until they are moderated by decay.

They--and the beard on my face.

Dialogue On a Dialogue

A: "Absorbed in rationalizing about immortality, we had let dusk

come without lighting the lamp. We could not see each other's

faces. He kept repeating that the soul is immortal, and the in-

difference and sweetness of Macedonia Ferminder's voice were

more convincing than fervor ever could have been. He was assur-

ing me that the death of the body is entirely insignificant and

that dying must perforce be the fact most null and void that

can happen to a man. I sat playing with Macedonio's clasp knife,

opening and closing it. A nearby accordion kept infinitely grind-

ing out La Cumparsita, that worn-out trifle loved by so many be-

cause they think it's old--I proposed that Macedonio and I commit

suicide so we could go on discussing without being bothered."

Z: (joking): "But I suspect that in the end you decided not to

do it."

A: (now fully mystical): "I don't really recall whether we com-

mitted suicide that night."

Argumentum Ornithologicum

I close my eyes and see a flock of birds. The vision lasts a sec-

ond or perhaps less; I don't know how many birds I saw. Were they

a definite or an indefinite number? This problem involves the

question of the existence of God. If God exists, the number is

definite, because how many birds I saw is known to God. If God

does not exist, the number is indefinite, because nobody was a-

ble to take count. In this case. I saw fewer than ten birds (let's

say) and more than one; but I did not see nine, eight, seven,

six, five, four, thine, or two birds. I saw a number between ten

and one, but not nine, eight, seven, six, five, etc. That number,

as a whole number, is inconceivable; ergo, God exists.

The Draped Mirrors

Islam asserts that on the unappealable day of judgment every

perpetrator of the image of a living creature will he raised

from the dead with his works, and he will be commanded to bring

them to life, and he will fail, and be cast out with them into

the fires of punishment. As a child. I felt before large mir-

rors that same horror of a spectral duplication or multipli-

cation of reality. Their infallible and continuous function-

ing, their pursuit of my actions, their cosmic pantomime,

were uncanny then, whenever it began to grow dark. One of

my persistent prayers to God and my guardian angel was that I

not dream about mirrors. I know I watched them with misgiv-

ings. Sometimes I feared they might begin to deviate from

reality; other times I was afraid of seeing there my own face,

disfigured by strange calamities. I have learned that this

fear is again monstrously abroad in the world. The story is

simple indeed, and disagreeable.

Around 1927 I met a sombre girl, first by telephone (for Ju-

lia began as a nameless, faceless voice), and, later, on a

corner toward evening. She had alarmingly large eyes, straight

blue-black hair. and an unbending body. Her grandfather and

great-grandfather were federales, as mine were unitarios,

and that ancient discord in our blood was for us a bond, a

fuller possession of the fatherland. She lived with her fam-

ily in a big old run-down house with very high ceilings, in

the vapidity and grudges of genteel poverty. Afternoons--some

few times in the evening -- we went strolling in her neigh-

borhood. Balvanera. We followed the thick wall by the rail-

road; once we walked along Sarmiento as far as the clearing

for the Porcine Centenario. There was no love between us, or

even pretense of love: I sensed in her an intensity that was

altogether foreign to the erotic, and I feared it. It is not un-

common to relate to women. in an urge for intimacy, true or a-

pochryphal circumstances of one's boyish past. I must have

told her once about the mirrors and thus in 1928 I prompted

a hallucination that was to flower in 1931 Now. I have just

learned that she has lost her mind and that the mirrors in

her room are draped because she sees in them my reflection,

usurping her own, and she trembles and falls silent and says

I am persecuting her by magic.

What bitter slavishness, that of my face, that of one of my

former faces. This odious fate reserved for my features must

perforce make me odious too, but I no longer care.

The Sham

It was one day in July, 1952, when the mourner appeared in

that little town in the Chaco. He was tall, thin, Indian-like,

with the inexpressive face of a mask or a dullard. People

treated him with deference, not for himself but rather for

the person he represented or had already become. He chose a

site near the river. With the help of some local women he set

up a board on two wooden horses and on top a cardboard box

with a blond doll in it. In addition, they lit four candles

in tall candlesticks and put flowers around. People were not

long in coming. Hopeless old women, gaping children, peasants

whose cork helmets were respectfully removed, filed past the

box and repeated, "Deepest sympathy, General." He, very sor-

rowful, received them at the head of the box, his hands cross-

ed over his stomach in the attitude of a pregnant woman. He

held out his right hand to shake the hands they extended to

him and replied with dignity and resignation: "It was fate.

Everything humanly possible was done." A tin money box receiv-

ed the two-peso fee, and many came more than once.

What kind of man, I ask myself, conceived and executed that

funereal farce? A fanatic, a pitiful wretch, a victim of hallu-

cinations, or an impostor and a cynic? Did he believe he was

Peron as he. played his suffering role as the macabre widower?

The story is incredible. but it happened. and perhaps not once

but many times, with different actors in different locales. It

contains the perfect cipher of an unreal epoch; it is like the

reflection of a dream or like that drama-within-the-drama we

see in Hamlet. The mourner was not Peron and the blond doll

was not the woman Eva Duarte, but neither was Peron Peron, nor

was Eva Eva. They were, rather, unknown individuals--or anon-

ymous ones whose secret names and true faces we do not know--

who acted out, for the credulous love of the lower middle classes,

a crass mythology.

Delia Elena San Marco

We said goodbye at the corner of Eleventh. From the other side-

walk I turned to look back; you too had turned, and you waved

goodbye to me.

A river of vehicles and people were flowing between us. It was

five o'clock on an ordinary afternoon. How was I to know that

that river was Acheron the doleful, the insuperable?

We did not see each other again, and a year later you were dead.

And now I seek out that memory and look at it, and I think it

was false, and that behind that trivial farewell was infinite

separation.

Last night I stayed in after dinner and reread, in order to un-

derstand these things, the last teaching Plato put in his master's

mouth. I read that the soul may escape when the flesh dies.

And now I do not know whether the truth is in the ominous sub-

sequent interpretation, or in the unsuspecting farewell.

For if souls do not die, it is right that we should not make

much of saying goodbye.

To say goodbye to each other is to deny separation. It is like

saying "today we play at separating, but we will see each other

tomorrow." Man invented farewells because he somehow knows he

is immortal, even though he may seem gratuitous and ephemeral.

Sometime, Delia, we will take up again--beside what river?--

this uncertain dialogue, and we will ask each other if ever,

in a city lost on a plain, we were Borges and Delia.

Dead Men's Dialogue

He arrived from southern England early one winter morning in

1877. Ruddy, athletic, and obese as he was, almost everyone in-

evitably thought he was English, and to tell the truth he was

remarkably like the archetypical John Bull. He wore a top hat

and a strange wool cape with an opening in the middle. A group

of men, women, and children anxiously waited for him. Many had

their throats marked with a red line; others were headless and

moved uncertainly, like a man walking in the dark. Little by

little they surrounded the stranger, and out of the crowd some-

one shouted an ugly word, but an ancient terror stopped them at

that. Then a military man with a yellowish skin and eyes like

firebrands stepped forward. His disheveled hair and murky beard

seemed to gobble up his face. Ten or twelve mortal wounds fur-

rowed his body like the stripes on a tiger's skin. The stranger,

seeing him, changed color suddenly; then he advanced and stretch-

ed out his hand.

"How it grieves me to see such an honorable warrior struck down

by the arms of treachery!" he said roundly. "But what an intimate

satisfaction, too, to have ordered that the acolytes who attended

the sacrifice should purge their deeds on the scaffold in Victoria

Square!"

"If you are speaking of Santos Perez and the Reinalits, I would

like you to know I have already thanked them," said the bloody one

with measured gravity.

The other man looked at him as if he suspected him of joking or

of making a threat, but Quiroga went on:

"Rosas, you never did understand me. And how could you. when our

destinies were so different? Your lot was to command in a city

that looks toward Europe and will someday be among the most famous

in the world. Mine was to wage war in America's lonely spots, on

poor earth belonging to poor gauchos. My empire was made of lances

and shouts and sand pits and almost secret victories in obscure

places. What claims are those to fame? I live and will continue to

live for many years in the people's memory because I was murdered

in a stagecoach at a place called Barranca Yaco, by horsemen armed

with swords. It is you I have to thank for this gift of a bizarre

death, which I did not know how to appreciate then, but which sub-

sequent generations have refused to forget. You undoubtedly know

of some exquisite lithographs, and the interesting book edited by

a worthy citizen of San Juan."

Rosas, who had recovered his aplomb, looked at him disdainfully.

"You are a romantic," he pronounced. "The flattery of posterity

is not worth much more than contemporary flattery, which is worth

nothing. and can be had on the strength of a few medals."

"I know your way of thinking," answered Quiroga. "In 1852, desti-

ny, either out of generosity or out of a desire to sound you to

your depths, offered you a real man's death in battle. You showed

yourself unworthy of that gift: the blood and fighting scared you."

"Scared?" repeated Rosas. "Me, who busted broncs in the South,

and later busted a whole country?"

For the first time Quiroga smiled.

"I know," he said slowly, "that you have cut more than one fine

figure on horseback, according to the impartial testimony of your

foremen and hands; but other fine figures were cut in America in

those days, and they were also on horseback—figures called Cha-

cabuco and Junin and Palma Redonda and Caseros."

Rosas listened without changing expression and replied:

"I did not have to be brave. One 'fine figure' of mine, as you

call it, was to manage that braver men than I should fight and

die for me. Santos Perez, for example, who finished you off. Brav-

ery is a question of holding out; some can hold out more than o-

thers, but sooner or later they all give in."

"That may he true," said Quiroga, "but I have lived and died and

to this day I do not know what fear is. And now I am going to be

obliterated, to be given another face and another destiny, for

history has had its fill of violent men. Who the other one will

be, what they will make of me, I do not know; but I know he will

not be afraid.

"I am satisfied to be who I am," said Rosas, "and I want to be

no one else."

"The stones want to be stones forever, too," said Quiroga, "and

for centuries they are, until they crumble into dust. I thought

as you do when I entered death, but I learned many things here.

Just look, we are both changing already."

But Rosas paid no attention and said, as if thinking aloud:

"It must be that I am not made to be a dead man, but these

places and this discussion seem like a dream, and not a dream

dreamed by me but by someone else still to be born."

They spoke no more, for at that moment Someone called them.

A Problem

Let us imagine that in Toledo someone finds a paper with an

Arabic text and that the paleographers declare the handwrit-

ing belongs to that same Cide Hamete Benengeli from whom

Cervantes took his Don Quixote. In the text we read that the

hero--who, the story goes, rambled about Spain armed with a

sword and a lance, challenging all sorts of people for all

sorts of reasons--discovers at the end of one of his many

frays that he has killed a man. At this point the fragment

breaks off. The problem is to guess, or to conjecture, how

Don Quixote reacts.

As I see it, there are three possible solutions. The first

is negative. Nothing special happens, for in the hallucina-

tory world of Don Quixote death is no less common than magic,

and to have killed a man need not perturb someone who strug-

gles, or thinks he struggles, with monsters and enchanters.

The second is pathetic. Don Quixote never managed to forget

that he was a projection of Alonso Quijano, a reader of fairy

tales. Seeing death, realizing that a dream has led him to

commit the sin of Cain, wakes him from his pampered madness,

possibly forever. The third is perhaps the most plausible.

Having killed the man, Don Quixote cannot admit that his ter-

rible act is the fruit of a delirium. The reality of the ef-

fect forces him to presuppose a parallel reality of the cause,

and Don Quixote will never emerge from his madness.

There remains another conjecture, alien to the Spanish world

and even to the Occidental world. It requires a much more an-

cient setting, more complex, and wearier. Don Quixote, who

is no longer Don Quixote but rather a king of the Hindustani

cycles, intuitively knows as he stands before his enemy's ca-

daver that to kill and to beget are divine or magical acts

which manifestly transcend humanity. He knows that the dead

man is an illusion, as is the bloody sword that weighs down

his hand, as is he himself, and all his past life, and the

vast gods, and the universe.

Martin Fierro

Out of this city marched armies that seemed to be great,

and afterwards were, when glory had magnified them. As the

years went by, an occasional soldier returned and, with a

foreign trace in his speech, told tales of what had happened

to him in places called Ituzaingo or Ayacucho. These things,

now, are as if they had never been.

Two tyrannies had their day here. During the first some men

coming from the Plata market hawked white and yellow peaches

from the seat of a cart. A child lifted a corner of the can-

vas that covered them and saw unitario heads with bloody

beards. The second, for many, meant imprisonment and death;

for all it meant discomfort, a taste of disgrace in everyday

acts, an incessant humiliation. These things, now, are as if

they had never been.

A man who knew all words looked with minute love at the

plants and birds of this land and described them, perhaps

forever, and wrote in metaphors of metal the vast chronicle

of the tumultuous sunsets and the shapes of the moon. These

things, now, are as if they had never been.

Here too the generations have known those common and somehow

eternal vicissitudes which are the stuff of art. These things,

now, are as if they had never been. But in a hotel room in

the 1860's, or thereabouts, a man dreamed about a fight. A gau-

cho lifts a Negro off his feet with his knife, throws him down

like a sack of bones, sees him agonize and die, crouches down

to clean his blade, unties his horse, and mounts slowly so he

will not be thought to be running away. This, which once was,

is again infinitely: the splendid armies are gone, and a lowly

knife fight remains. The dream of one man is part of the memory

of all.

Mutations

I saw in a hall an arrow pointing the way and I thought that this

inoffensive symbol had once been a thing of iron, an in-escapable

and fatal projectile that pierced the flesh of men and of lions

and clouded the sun at Thermopylae and gave Harald Sigurdarson

six feet of English earth forever.

Some days later someone showed me a photograph of a Magyar horse-

man. A coiled lasso circled the breast of his mount. I learned

that the lasso, which once whipped through the air and brought

down the bulls of the prairie, was now nothing more than a haughty

trapping of Sunday harness.

In the west cemetery I saw a runic cross, chiseled in red marble.

The arms curved as they widened out, and a circle encompassed them.

That limited, circumscribed cross represented the other one, the

free-armed cross, which in its turn represents the gallows where

a god suffered, the "vile machine" railed at by Lucian of Samosata.

Cross, lasso, and arrow—former tools of man, debased or exalted

now to the status of symbols. Why should I marvel at them, when

there is not a single thing on earth that oblivion does not erase

or memory change, and when no one knows into what images he himself

will be transmuted by the future.

Parable of Cervantes and Don Quixote

Weary of his land of Spain, an old soldier of the king sought sol-

ace in Ariosto's vast geographies, in that valley of the moon where

misspent dream-time goes, and in the golden idol of Mohammed stolen

by Montalbin.

In gentle mockery of himself he conceived a credulous man who, un-

settled by the marvels he read about, hit upon the idea of seeking

noble deeds and enchantments in prosaic places called El Toboso or

Montiel.

Defeated by reality, by Spain, Don Quixote died in his native vill-

age around 1614 He was survived only briefly by Miguel de Cervantes.

For both of them, for the dreamer and the dreamed, the tissue of

that whole plot consisted in the contraposition of two worlds: the

unreal world of the books of chivalry and the common everyday world

of the seventeenth century.

Little did they suspect that the years would end by wearing away the

disharmony. Little did they suspect that La Mancha and Montiel and

the knight's frail figure would be, for the future, no less poetic

than Sindbad's haunts or Ariosto's vast geographies.

For myth is at the beginning of literature, and also at its end.

Devoto Clink, January 1955.

Ragnara

In dreams, writes Coleridge, images represent the sensations we

think they cause: we do not feel horror because we are threatened

by a sphinx; we dream of a sphinx in order to explain the horror

we feel. If this is so, how could a mere chronide of the shapes that

that night's dream took communicate the bewilderment, the exaltation,

the alarm, the menace, and the jubilation that wove it together?

None the less, I shall attempt that chronicle. Perhaps the fact that

a single scene united the dream will remove or alleviate the essen-

tial difficulty.

The scene was the College of Philosophy and Letters, the hour

twilight As usual in dreams, everything was a little different; a

slight enlargement altered things. We were electing officers. I was

talking with Pedro Henriquez Urefia, who in the waking world has

been dead for many years. Suddenly we were interrupted by a clamor

as of a demonstration or a band of street musicians. Howls, both an-

imal and human, rose from Below. A voice cried out, "Here they come!"

and then, "The Gods! The Gods!" Four or five fellows emerged from

the mob and took over the platform of the assembly hall. We all ap-

plauded, weeping: these were the Gods, returning after a centuries-

long exile. Exalted by the platform, their heads thrown back and

their chests out, they haughtily received our homage. One was hold-

ing a branch which conformed, no doubt, to the simple botany of

dreams; another, in a broad gesture, held out his hand—a claw; one

of the faces of Janus looked suspiciously at the curved beak of

Thoth. Goaded perhaps by our applause, one, I do not know which,

broke out in a victorious and incredibly bitter cackle, half gargle,

half whistle. From that moment on, things changed.

It all began with the suspicion, perhaps exaggerated, that the Gods

could not talk. Centuries of brutish and bloodthirsty life had atro-

phied whatever there had been of the human in them. Islam's moon and

Rome's cross had dealt implacably with those fugitives. Low foreheads,

yellow teeth, sparse mustaches like a mulatto's or a Chinaman's, and

thick bestial lips bespoke the degeneration of the Olympian lineage.

Their garments were less suited to decorous, decent poverty than to the

evil sumptuousness of the gambling dens and bawdy houses of Below. In

the buttonhole of one bled a red carnation; beneath the tight-fitting

jacket of another bulged the form of a dagger. Suddenly we felt they

were playing their last card, that they were crafty, ignorant, and

cruel as old beasts of prey, and that if we allowed ourselves to be

won over by fear or pity, they would end by destroying us.

We drew our heavy revolvers—all at once there were revolvers in the

dream—and joyously put the Gods to death.

Poem about Gifts

Let none think I by tear or reproach make light

Of this manifesting the mastery

Of God, who with excelling irony

Gives me at once both books and night

In this city of books he made these eyes

The sightless rulers who can only read,

In libraries of dreams, the pointless

Paragraphs each new dawn offers

To awakened care. In vain the day

Squanders on them its infinite books,

As difficult as the difficult scripts

That perished in Alexandria.

An old Greek story tells how some king died

Of hunger and thirst, though proffered springs and fruits;

My bearings lost, I trudge from side to side

Of this lofty, long blind library.

The walls present, but uselessly,

Encyclopaedia, atlas, Orient

And the West, all centuries, dynasties,

Symbols, cosmos, and cosmogonies.

Slow in my darkness, I explore

The hollow gloom with my hesitant stick,

I, that used to figure Paradise

In such a library's guise.

Something that surely cannot be called

Mere chance must rule these things;

Some other man has met this doom

On other days of many books and the dark.

As I walk through the slow galleries

I grow to feel with a kind of holy dread

That I am that other, I am the dead,

And the steps I make are also his.

The Hourglass

It is well that time can be measured

With the harsh shadow a column in summer

Casts, or the water of that river

In which Heraclitus saw our folly,

Since both to time and destiny

The two seem alike: the unweighable daytime

Shadow, and the irrevocable course

Of water following its own path.

It is well, but time in the desert

Found another substance, smooth and heavy,

That seems to have been imagined

For measuring dead men's time.

Hence the allegorical instrument

Of the dictionary illustrations,

The thing that gray antiquaries

Will consign to the red-ash world

Of the odd chess-bishop, of the sword

Defenseless, of the telescope bleared,

Of sandalwood eroded by opium,

Of dust, of hazard, of the nada.

Who has not paused before the severe

And sullen instrument accompanying

The scythe in the god's right hand

Whose outlines Duerer etched?

Through the open apex the inverted cone

Lets the minute sand fall down,

Gradual gold that loosens itself and fills

The concave crystal of its universe.

There is pleasure in watching the recondite

Sand that slides away and slopes

And, at the falling-point, piles up

With an urgency wholly human.

The sand of the cycles is the same,

And infinite, the history of sand;

Thus, deep beneath your joys and pain

Unwoundable eternity is still the abyss.

Never is there a halt in the fall.

It is I lose blood, not the glass. The ceremony

Of drawing off the sand goes on forever

And with the sand our life is leaving us.

In the minutes of the sand I believe

I feel the cosmic time: the history

That memory locks up in its mirrors

Or that magic Lethe has dissolved.

The pillar of smoke and the pillar of fire,

Carthage and Rome and their crushing war,

Simon Magus, the seven feet of earth

That the Saxon proffered the Norway king,

This tireless subtle thread of unnumbered

Sand degrades all down to loss.

I cannot save myself, a come-by-chance

Of time, being matter that is crumbling.

The Game of Chess

I

In their grave corner, the players

Deploy the slow pieces.

And the chessboard

Detains them until dawn in its severe

Compass in which two colors hate each other.

Within it the shapes give off a magic

Strength: Homeric tower, and nimble

Horse, a fighting queen, a backward king,

A bishop on the bias, and aggressive pawns.

When the players have departed, and

When time has consumed them utterly,

The ritual will not have ended.

That war first flamed out in the east

Whose amphitheatre is now the world.

And like the other, this game is infinite.

II

Slight king, oblique bishop, and a queen

Blood-lusting; upright tower, crafty pawn—

Over the black and the white of their path

They foray and deliver armed battle.

They do not know it is the artful hand

Of the player that rules their fate,

They do not know that an adamant rigor

Subdues their free will and their span.

But the player likewise is a prisoner

(The maxim is Omar's) on another board

Of dead-black nights and of white days.

God moves the player and he, the piece.

What god behind God originates the scheme

Of dust and time and dream and agony?

Mirrors

I, who felt the horror of mirrors

Not only in front of the impenetrable crystal

Where there ends and begins, uninhabitable,

An impossible space of reflections,

But of gazing even on water that mimics

The other blue in its depth of sky,

That at times gleams back the illusory flight

Of the inverted bird, or that ripples,

And in front of the silent surface

Of subtle ebony whose polish shows

Like a repeating dream the white

Of something marble or something rose,

Today at the tip of so many and perplexing

Wandering years under the varying moon,

I ask myself what whim of fate

Made me so fearful of a glancing mirror.

Mirrors in metal, and the masked

Mirror of mahogany that in its mist

Of a red twilight hazes

The face that is gazed on as it gazes,

I see them as infinite, elemental

Executors of an ancient pact,

To multiply the world like the act

Of begetting. Sleepless. Bringing doom.

They prolong this hollow, unstable world

In their dizzying spider's-web;

Sometimes in the afternoon they are blurred

By the breath of a man who is not dead.

The crystal spies on us. If within the four

Walls of a bedroom a mirror stares,

I'm no longer alone. There is someone there.

In the dawn reflections mutely stage a show.

Everything happens and nothing is recorded

In these rooms of the looking glass,

Where, magicked into rabbis, we

Now read the books from right to left.

Claudius, king of an afternoon, a dreaming king,

Did not feel it a dream until that day

When an actor shewed the world his crime

In a tableau, silently in mime.

It is strange to dream, and to have mirrors

Where the commonplace, worn-out repertory

Of every day may include the illusory

Profound globe that reflections scheme.

God (I keep thinking) has taken pains

To design that ungraspable architecture

Reared by every dawn from the gleam

Of a mirror, by darkness from a dream.

God has created nighttime, which he arms

With dreams, and mirrors, to make clear

To man he is a reflection and a mere

Vanity. Therefore these alarms.

Elvira de Alvear

All things she possessed and slowly

All things left her. We have seen her

Armed with loveliness. The morning

And the strenuous midday showed her,

At her summit, the handsome kingdoms

Of the earth. The afternoon was clouding them.

The friendly stars (the infinite

And ubiquitous mesh of causes) granted her

That wealth which annuls all distance

Like the magic carpet, and which makes

Desire and possession one; and a skill in verse

That transforms our actual sorrows

Into a music, a hearsay, and a symbol;

And granted fervor, and into her blood the battle

Of Ituzaingo and the heaviness of laurels;

And the joy of losing herself in the wandering

River of time (river and labyrinth),

And in the slow tints of afternoons.

All things left her, all

But one. Her highborn courtliness

Accompanied her to the end of the journey,

Beyond the rapture and its eclipse,

In a way like an angel's. Of Elvira

The first thing that I saw, such years ago,

Was her smile and also it was the last.

Susana Soca

With slow love she looked at the scattered

Colors of afternoon. It pleased her

To lose herself in intricate melody

Or in the curious life of verses.

Not elemental red but the grays

Spun her delicate destiny,

Fashioned to discriminate and exercised

In vacillation and in blended tints.

Without venturing to tread this perplexing

Labyrinth, she watched from without

The shapes of things, their tumult and their course,

Just like that other lady of the mirror.

Gods who dwell far-off past prayer

Abandoned her to that tiger, Fire.

The Rain

The afternoon grows light because at last

Abruptly a minutely shredded rain

Is falling, or it fell. For once again

Rain is something happening in the past.

Whoever hears it fall has brought to mind

Time when by a sudden lucky chance

A flower called "rose" was open to his glance

And the curious color of the colored kind.

This rain that blinds the windows with its mists

Will gladden in suburbs no more to be found

The black grapes on a vine there overhead

In a certain patio that no longer exists.

And the drenched afternoon brings back the sound

How longed for, of my father's voice, not dead.

On the Effigy of a Captain in Cromwell's Armies

The battlements of Mars no longer yield

To him whom choiring angels now inspire;

And from another light (and age) entire

Those eyes look down that viewed the battlefield.

Your hand is on the metal of your sword.

And through the green shires war stalks on his way;

They wait beyond that gloom with England still,

Your mount, your march, your glory of the Lord.

Captain, your eager cares were all deceits,

Vain was your armor, vain the stubborn will

Of man, whose term is but a little day;

Time has the conquests, man has the defeats.

The steel that was to wound you fell to rust;

And you (as we shall be) are turned to dust.

To an Old Poet

You walk the Castile countryside

As if you hardly saw that it was there.

A tricky verse of John's your only care,

You scarcely notice that the sun has died

In a yellow glow. The light diffuses, trembles,

And on the borders of the East there spreads

That moon of mockery which most resembles

The mirror of Wrath, a moon of scarlet-reds.

You raise your eyes and look. You seem to note

A something of your own that like a bud

Half-breaks then dies. You bend your pallid head

And sadly make your way--the moment fled--

And with it, unrecalled, what once you wrote:

And for his epitaph a moon of blood.

Blind Pew

Far from the sea and from fine war,

Which love hauled with him now that they were lost,

The blind old buccaneer was trudging

The cloddy roads of the English countryside.

Barked at by the farmhouse curs,

The butt of all the village lads,

In sickly and broken sleep he stirred

The black dust in the wayside ditches.

He knew that golden beaches far away

Kept hidden for him his own treasure,

So cursing fate's not worth the breath;

You too on golden beaches far away

Keep for yourself an incorruptible treasure:

Hazy, many-peopled death.

Referring to a Ghost of

Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-Odd

Nothing. Only Murafia's knife.

Only in the gray afternoon the story cut short.

I don't know why in the afternoons I'm companioned

By this assassin that I've never seen.

Palermo was further down. The yellow

Thick wall of the jail dominated

Suburb and mud flat. Through this savage

District went the sordid knife.

The knife. The face has been smudged out

And of that hired fellow whose austere

Craft was courage, nothing remained

But a ghost and a gleam of steel.

May time, that sullies marble statues,

Salvage this staunch name: Juan Murafia.

Referring to the Death of

Colonel Francisco Borges (1835--.1874)

I leave him on his horse, and in the gray

And twilit hour he fixed with death for a meeting;

Of all the hours that shaped his human day

May this last long, though bitter and defeating.

The whiteness of his horse and poncho over

The plain advances. Setting sights again

To the hollow rifles death lies under cover.

Francisco Borges sadly crosses the plain.

This that encircled him, the rifles' rattle,

This that he saw, the pampa without bounds,

Had been his life, his sum of sights and sounds.

His every-dailiness is here and in the battle.

I leave him lofty in his epic universe

Almost as if not tolled for by my verse.

The Borges

I know little--or nothing--of my own forebears;

The Borges back in Portugal; vague folk

That in my flesh, obscurely, still evoke

Their customs, and their firmnesses and fears.

As slight as if they'd never lived in the sun

And free from any trafficking with art,

They form an indecipherable part

Of time, of earth, and of oblivion.

And better so. For now, their labors past,

They're Portugal, they are that famous race

Who forced the shining ramparts of the East,

And launched on seas, and seas of sand as wide.

The king they are in mystic desert place,

Once lost; they're one who swears he has not died.

In Memoriam : A. R.

Vague chance or the precise laws

That govern this dream, the universe,

Granted me to share a smooth

Stretch of the course with Alfonso Reyes.

He knew well that art which no one

Wholly knows, neither Sindbad nor Ulysses,

Which is to pass from one land on to others

And yet to be entirely in each one.

If memory ever did with its arrow

Pierce him, he fashioned with the intense

Metal of the weapon the rhythmical, slow

Alexandrine or the grieving dirge.

In his labors he was helped by mankind's

Hope, which was the light of his life,

To create a line that is not to be forgotten

And to renew Castilian prose.

Beyond the Myo Cid with slow gait

And that flock of folk that strive to be obscure,

He tracked the fugitive literature

As far as the suburbs of the city slang.

In the five gardens of the Marino

He delayed, but he had something in him

Immortal, of the essence which preferred

Arduous studies and diviner duties.

To put it better, he preferred the gardens

Of meditation, where Porphyry

Reared before the shadows and delight

The Tree of the Beginning and the End.

Reyes, meticulous providence

That governs the prodigal and the thrifty

Gave some of us the sector or the arc,

But to you the whole circumference.

You sought the happy and the sad

That fame or frontispieces hide;

Like the God of Erigena you desired

To be no man so that you might be all.

Vast and delicate splendors

Your style attained, that manifest rose,

And turned that fighting blood of your forebears

Into cheerful blood to wage in God's own wars.

Where (I ask) will the Mexican be?

Will he contemplate with Oedipus' horror

Before the stranger Sphinx, the unmoving

Archetype of Visage and of Hand?

Or is he wandering, as Swedenborg says,

Through a world more vivid and complex

Than our earthly one, which is scarcely the reflex

Of that high, celestial something impenetrable?

If (as the empires of lacquer

And ebony teach) man's memory shapes

Its own Eden within, there is now in glory

One Mexico more, another Cuernavaca.

God knows the colors that fate

Has in store for man beyond his day;

I walk these streets--and yet how little

Do I catch up with the meaning of death.

One thing alone I know. That Alfonso Reyes

(Wherever the sea has brought him safe ashore)

Will apply himself happy and watchful

To other enigmas and to other laws.

Let us honor with the palms and the shout

Of victory the peerless and unique;

No tears must shame the verse

Our love inscribes to his name.

To Luis de Camoins

Without lament or anger time will nick

The most heroic swords. Poor and in sorrow,

You came home to a land turned from tomorrow,

O captain, came to die within her, sick,

And with her. In the magic desert-wastes

The flower of Portugal was lost and died,

And the harsh Spaniard, hitherto subdued,

Was menacing her naked, open coasts.

I wish I knew if on this hither side

Of the ultimate shore you humbly understood

That all that was lost, the Western Hemisphere

And the Orient, the steel and banner dear,

Would still live on (from human change set free)

In your epic Lusiados timelessly.

Nineteen hundred and Twenty-Odd

The wheeling of the stars is not infinite

And the tiger is one of the forms that return.

But we, remote from chance or hazard.

Believed we were exiled in a time outworn,

Time when nothing can happen.

The universe, the tragic universe, was not here

And maybe should be looked for somewhere else;

I hatched a humble mythology of fencing

walls and knives

And Ricardo thought of his drovers.

We did not know that time to come held a lightning bolt;

We did not foresee the shame, the fire, and the fearful

night of the Alliance;

Nothing told us that Argentine history would be thrust

out to walk the streets,

History, indignation, love.

The multitudes like the sea, the name of Cordoba,

The flavor of the real and the incredible, the

horror and the glory.

Ode Composed in 1960

Sheer accident or the secret laws

That rule this dream, my destiny,

Will-0 needed and sweet homeland

That not without glory and without shame embrace

A hundred and fifty arduous years—

That I, the drop, should speak with you, the river,

That I, the instant, speak with you, who are time,

And that the intimate dialogue resort,

As the custom is, to the rites and the dark hints

Beloved of the gods, and to the decorum of verse.

My country, I have sensed you in the tumbledown

Decadence of the widespread suburbs,

And in that thistledown that the pampas wind

Blows into the entrance hall, and in the patient rain,

And in the slow coursing of the stars,

And in the hand that tunes a guitar,

And in the gravitation of the plain

That, from however far, our blood feels

As the Briton feels the sea, and in the pious

Symbols and urns of a vault.

And in the gallant love of jasmine,

And in the silver of a picture-frame and the polished

Rubbing of the silent mahogany,

And in the flavors of meat and fruits,

And in a flag sort of blue and white

Over a barracks, and in unappetizing stories

Of street-corner knifings, and in the sameness

Of afternoons that are wiped out and leave us,

And in the vague pleased memory

Of patios with slaves bearing

The name of their masters, and in the poor

Leaves of certain books for the blind

That fire scattered, and in the fall

Of those epic rains in September

That nobody will forget---but these things

Are not wholly you yourself nor yet your symbols.

You are more than your wide territory

And more than the days of your unmeasured time,

You are more than the unimaginable sum

Of your children after you. We do not know

What you are for God in the living

Heart of the eternal archetypes,

But by this imperfectly glimpsed visage

We live and die and have our being--

O never-from-me and mystery-my-country.

On Beginning the Study of Anglo-Saxon Grammar

At fifty generations' end

(And such abysses time affords us all)

I return to the further shore of a great river

That the vikings' dragons did not reach,

To the harsh and arduous words

That, with a mouth now turned to dust,

I used in my Northumbrian, Mercian days

Before I became a Haslam or Borges.

On Saturday we read that Julius Caesar

Was the first man out of Romeburg to strip the

veil from England;

Before the clusters swell again on the vine

I shall have heard the voice of the nightingale

With its enigma, and the elegy of the warrior twelve

That surround the tomb of their king.

Symbols of other symbols, variations

On the English or German future seem these words to me

That once on a time were images

A man made use of praising the sea or a sword;

Tomorrow they will live again.

Tomorrow fyr will not be fire but that form

Of a tamed and changing god

It has been given to none to see without an ancient dread.

Praised be the infinite

Mesh of effects and causes

Which, before it shews me the mirror

In which I shall see no-one or I shall see another,

Grants me now this contemplation pure

Of a language of the dawn.

Adrogue

Let no fear be that in indecipherable night

I shall lose myself among the black flowers

Of the park, where the secret bird that sings

The same song over and over, the round pond,

And the summerhouse, and the indistinct

Statue and the hazardous ruin. weave

Their scheme of things propitious to the languor

Of afternoons and to nostalgic loves.

Hollow in the hollow shade, the coachhouse

Marks (I know) the tremulous confines

Of this world of dust and jasmine.

Pleasing to Verlaine, pleasing to Julio Herrera.

The eucalyptus trees bestow on the gloom

Their medicinal smell: that ancient smell

That, beyond all time and the ambiguity

Of language, speaks of manorhouse time.

My footstep seeks and finds the hoped-for

Threshold. The flat roof there defines

its darkened edge, and in measured time the tap

In the checkered patio slowly drips.

On the other side of the door they sleep.

Those who by means of dreams

In the visionary darkness are masters

Of the long yesterday and of all things dead.

I know every single object of this old

Building: the flakes of mica

On that gray stone that doubles itself

Endlessly in the smudgy mirror

And the lion's head that bites

A ring and the stained glass windows

That reveal to a child wonders

Of a crimson world and another greener world.

For beyond all chance and death

They endure, each one with its history,

But all this is happening in that destiny

Of a fourth dimension, which is memory.

In that and there alone now still exist

The patios and the gardens. And the past

Holds them in that forbidden round

Embracing at one time vesper and dawn.

How could I lose that precise

Order of humble and beloved things,

As out of reach today as the roses

That Paradise gave to the first Adam?

The ancient amazement of the elegy

Loads me down when I think of that house

And I do not understand how time goes by,

I, who am time and blood and agony.

Museum

On Rigor in Science

In that Empire, the Art of Cartography reached such Perfection

that the map of one Province, alone took up the whole of a City,

and the map of the empire, the whole of a Province. In time, those

Unconscionable Maps did not satisfy and the Colleges of Cartograph-

ers set up a Map of the Empire which had the size of the Empire

itself and coincided with it point by point. Less Addicted to the

Study of Cartography, Succeeding Generations understood that this

Widespread Map was Useless and not without Impiety they abandoned

it to the Inclemencies of the Sun and of the Winters. In the des-

erts of the West some mangled Ruins of the Map lasted on, inhabit-

ed by Animals and Beggars; in the whole Country there are no other

relics of the Disciplines of Geography.

Suarez Miranda: Violet tie Varones Prudentes, Book Four, Chapter

XLV, Lerida, t638.

Quatrain

Others died, but it happened in the past,

The season (as all men know) most favorable for death.

Is it possible that I, subject of Yaqub Almansur,

Must die as roses had to die and Aristotle?

Limits

There is a line in Verlaine I shall not recall again.

There is a street close by forbidden to my feet,

There's a mirror that's seen me for the very last time,

There is a door that I have locked till the end of the world.

Among the books in my library (I have them before me)

There are some that I shall never open now.

This summer I complete my fiftieth year;

Death is gnawing at me ceaselessly.

Julio Platero Hawks: Interipciones (Montevideo, 1923)

The Poet Declares His Renown

The circle of the sky metes out my glory,

The libraries of the East contend for my poems,

Emirs seek me out to fill my mouth with gold,

Angels already know by heart my latest ghazal.

My working tools are humiliation and an anguish;

Would to God I'd been stillborn.

From the Divan of Abulcasirn Fl liadrami(12th century)

The Magnanimous Enemy

Magnus Barfod, in the year 1102, undertook the general conquest

of the kingdoms of Ireland; it is said that on the eve of his death

he received this greeting from Muirchertach, king in Dublin:

May gold and the storm fight along with you in your armies.

Magnus Barfod.

Tomorrow, in the fields of my kingdom, may you have a

happy battle.

May your kingly hands be terrible in weaving the sword-stuff.

May those opposing your sword become meat for the red swan.

May your many gods glut you with glory, may they glut you

with blood.

Victorious may you be in the dawn, king who tread on Ireland.

Of your many days may none shine bright as tomorrow.

Because that day will be the last. I swear it to you,

King Magnus.

For before its light is blotted, I shall vanquish you and blot you

out, Magnus Barfod.

From IL Gering: Anhang zur Heimskringla (1893)

The Regret of Heraclitus

I, who have been so many men, have never been

The one in whose embrace Matilde Urbach swooned.

Gaspar Carmerarius, in Deliciae poetarum Borussiae, VII, 13

Epilogue

God grant that the essential monotony of this miscellany (which time

has compiled—not I-and which admits past pieces that I have not dared

to revise, because I wrote them with a different concept of litera-

ture) be less evident than the geographical and historical diversity

of its themes. Of all the books I have delivered to the presses, none,

I think, is as personal as the straggling collection mustered for

this hodge-podge, precisely because it abounds in reflections and inter-

polations. Few things have happened to me, and I have read a great many.

Or rather, few things have happened to me more worth remembering than

Schopenhauer's thought or the music of England's words.

A man sets himself the task of portraying the world. Through the years

he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays,

ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and people.

Shortly before his death, he discovers that that patient labyrinth of

lines traces the image of his face.

J. LB.

Buenos Aires, October 31, 1960.